Book Review: Going Beyond the Great Van Gogh Hagiography Machine

By Allen Michie

Émile Bernard, to his credit, spends much of his life redeeming rather than demeaning his friend.

My Friend Van Gogh by Émile Bernard. Translated from the French by Elizabeth G. Heard with an introduction by Martin Bailey. David Zwirner Books, 112 pages, $15.

Émile Bernard and Vincent Van Gogh (back to the camera) on the banks of the Seine at Asnieres, 1886. Photo: Wiki Common

Some say that this is the only photograph of Vincent Van Gogh as an adult, having a drink with his young friend and fellow painter Émile Bernard along the river Seine in 1886. If it is, it’s appropriate that Van Gogh is a figure of darkness, at once casual and unknowable, his face hidden. Bernard, appropriately as well, is alert and attentive. All the better that the two artists appear in a photo that is divided by a strong vertical line that balances the receding horizontal lines of the horizon. An anonymous figure in the middle distance sets the perspective, infusing some life to the otherwise barren scene. Picturesque smokestacks in the far distance and some evenly placed scraggly trees make it even more like a Van Gogh painting.

The reality is that Van Gogh was likely never this stocky. He preferred his weather-beaten straw hat and painter’s frock, and if he was out on the Seine, he would have been there to paint. There is no easel nearby. Most biographical scholars ignore this picture.

But the first interpretation makes such a lovely myth — we want to see Van Gogh as he really was. The artist who left us so many revelatory self-portraits and confessional letters remains opaque in ways that matter little to his art but matter a great deal to his position as perhaps the world’s most popular artist. What was the source and nature of his mental illness? Why did he mutilate his ear? Why did he (supposedly) commit suicide, at the height of his powers, just at the beginning his emerging fame? Whereas most people care about the lives of artists only as much as they inform us about their paintings, we cannot help but see Van Gogh’s paintings as cryptic keys to what they tell us about the man.

The Van Gogh most think of today — the sensitive genius who was too beautiful for this world, as Don McClean sings in “Vincent,” or the teary-eyed artist overcome with humble emotion in a memorable Doctor Who episode — is no doubt partially true to life. What is also true: Van Gogh could be an ornery, exasperating, anti-social, sexist, and fanatical man who smoked and drank to the point that his teeth fell out. But the version of Van Gogh that we honor today is the result of a careful and deliberate construction that began almost immediately after Van Gogh’s death in 1890. It’s a rare case of history remembering a complex man at his best rather than his worst, something it would be nice to see happen more often.

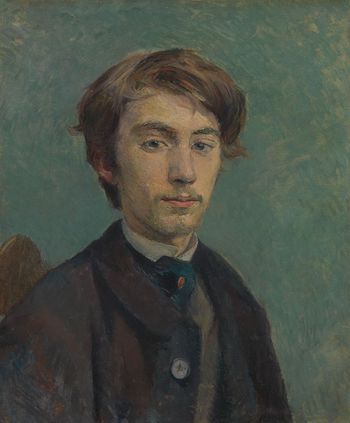

The man who first fired up the Great Van Gogh Hagiography Machine, still humming along nicely in art museum gift shops around the world today, was Émile Bernard. He was an intelligent and precocious artistic talent, just 18 when he first met Van Gogh at an art school (Van Gogh was far too cantankerous and independently minded to last long under anyone’s tutelage). He was 15 years younger than Van Gogh. The elder sometimes assumed a paternalistic attitude, but they came to respect one another as artistic equals. “Young Bernard — according to me — has already made a few absolutely astonishing canvases in which there’s a gentleness and something essentially French and candid, of rare quality,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo.

The man who first fired up the Great Van Gogh Hagiography Machine, still humming along nicely in art museum gift shops around the world today, was Émile Bernard. He was an intelligent and precocious artistic talent, just 18 when he first met Van Gogh at an art school (Van Gogh was far too cantankerous and independently minded to last long under anyone’s tutelage). He was 15 years younger than Van Gogh. The elder sometimes assumed a paternalistic attitude, but they came to respect one another as artistic equals. “Young Bernard — according to me — has already made a few absolutely astonishing canvases in which there’s a gentleness and something essentially French and candid, of rare quality,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo.

During the two years (1886-88) that Van Gogh lived with Theo in Paris, Van Gogh and Bernard painted together, exhibited together, and helped one another professionally via Theo’s art dealership and contacts in the Paris art world. Van Gogh was a man of few friends, but Bernard was, for a time, his best one. They exchanged letters and drawings after Paris, letters which included some of Van Gogh’s significant ruminations about artistic technique, color theory, art history, and the purpose of painting.

Before photographs became common, artists had to describe their work and provide summary sketches to one another. The letters to Bernard have some of Van Gogh’s most vivid and poetic descriptions of his work and justifications for his choices. “Another canvas depicts a sun rising over a field of new wheat,” Van Gogh wrote on Nov. 26, 1989. “Receding lines in the furrows run high up on the canvas, toward a wall and a range of lilac hills. The field is violet and green-yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole. In it, in contrast to the other canvas, I have tried to express calm, a great peace.”

Eventually, in 1889, Van Gogh exhausted Bernard’s patience via insults to the latter’s penchant for religious art subjects (reversing a strongly held earlier opinion, which Van Gogh did with almost clockwork regularity). Van Gogh was absorbed in the present, in the sensations around him; they were far too overpowering to allow much time for historical subjects. “I ask you one last time, shouting at the top of my voice: please try to be yourself again!” The letter ended their friendship, and (to our knowledge) they never corresponded again.

But Bernard didn’t hold a grudge, and he was one of the few guests at Van Gogh’s funeral. Immediately upon arriving at the wake, he began rearranging the paintings Theo had put on display. Right away, it was as if he assumed a right to control how Van Gogh would be presented. It’s a right that belonged to Theo, or by extension, Theo’s wife Jo (who exercised that responsibility generously and wisely after Theo’s death just six months later). But Bernard had good intentions; he was determined to honor Theo’s wish to launch the first major Van Gogh exhibition and assert the artist’s mastery. Bernard organized the show, investing all of his hard-won cultural caché behind it.

Bernard’s complete writings about Van Gogh are now collected in a new slender volume, My Friend Van Gogh, edited by the imminent Van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey and translated from the French by Elizabeth G. Heard. The book is the first full English translation of Bernard’s 1911 Lettres de Vincent van Gogh à Émile Bernard, which consisted of four of Bernard’s earlier introductions to Van Gogh’s letters, plus a new extended preface. This volume is a complete translation of Bernard’s writing in Lettres de Vincent van Gogh à Émile Bernard, but it rearranges Bernard’s texts in chronological order. It also adds a very small selection of letters from Van Gogh to Bernard (Bernard’s letters to Van Gogh have not survived). It’s not a scholarly edition with notes and apparatus, and Bailey’s short introduction is mostly limited to biographical and historical context.

“Sometimes Bernard’s details are not quite correct, and at other times he certainly exaggerates the importance of his own art and role, but I would argue that he is a relatively reliable source on Van Gogh,” Bailey writes in his introduction. For all the positive early attention Bernard cultivated for Van Gogh, however, he has a lot to answer for. He falsified the Van Gogh legend in ways that remain entrenched to this day. He sent a sensationally fictionalized account of the ear incident to the muckraking art critic Albert Aurier. Bernard was being self-serving here — he degraded Van Gogh to court the attention of the influential critic whom he had long been pursuing to help make himself and his Neo-Impressionist friends be seen as a viable “movement” in Paris art circles. He cranked it up, writing to Aurier that Van Gogh believed “he was some kind of Christ, a God” and “a being from the other side.”

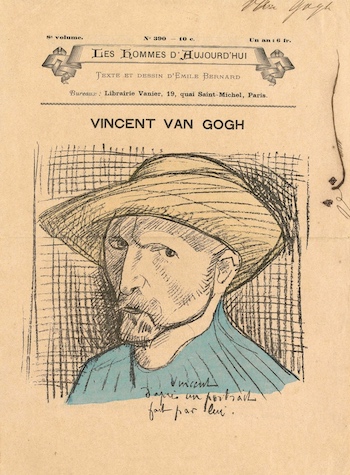

Vincent Van Gogh par Émile Bernard, 1892. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) Sketch done in July 1891.

He went on to insist that Van Gogh’s madness drove him to visions. And he accused Gauguin of trying to murder Van Gogh. (The letter backfired: Aurier hewed to the decadent tortured genius archetype version of Van Gogh.) Bernard was the first to put in print the dubious idea that Van Gogh committed suicide, which he stated as fact –and he did so in a letter to Aurier, who was pretty much a gossip columnist. The romantic assumption — a tortured Van Gogh killed himself — is far more compelling than the prosaic truth: that he was shot by a careless punk show-off who liked to play Buffalo Bill and wave around his loaded broken gun. The myth remains engrained to this day. Bailey states the suicide as a fact in his introduction.

It’s fascinating to read the texts in chronological order to see Bernard working through what critic Harold Bloom would have called his “anxiety of influence.” Bernard, to his credit, spends much of his life redeeming rather than demeaning his friend. The first four entries are short prefaces to selections of Van Gogh’s letters that appeared in magazines or to volumes of the selected correspondence (one of which was not published). In the five entries from 1893 to 1911, Bernard’s judgments mature. We can see turn away from the urge to shape perceptions of Van Gogh’s life and personality to a much deeper and more open-minded relationship to Van Gogh’s aesthetic ideas: “Nothing was farther from my blind absolutism than Vincent’s eclecticism. Now I acknowledge his wisdom.”

In the first preface, Bernard doesn’t provide much more than a biographical sketch. From the beginning, however, Bernard has an uncannily prescient appreciation of Van Gogh’s style. Words that might seem commonplace about Van Gogh today would have been brave, original, and brilliant assertions in 1891. Bernard has the early wisdom to feel his way through the paintings. It’s worth quoting at length for what it can tell us about how to see Van Gogh’s art, both then and now (and also for a demonstration of the fine poetry in Heard’s English translation):

There is inspiration in the biblical harvests depicted at twilight; the sheaves, laden with seeds, are heaped into vast mounds; their blades wave like golden banners. We feel sadness before those dark cypresses and the magnetic spears that fix the stars with their points; we marvel at nights like pyrotechnic symphonies sparkling in the shadows of an ultramarine sky. Then we dream beneath groves of flowers that glitter like fallen stars. On a peaceful bank, we see a river that flows without a ripple toward mournful foothills, passing cottages veiled by willows. Having experienced this wave of emotion, we study the eyes of the sitters in his portraits. We see the acknowledgment of lives that are sad or shameful, benign or sinister. Then we will be on the path to understanding Vincent and admiring his work.

The second preface, published in the Mercure de France magazine in 1893, makes a forceful argument for Van Gogh’s role starting Impressionism. “The letters written to Theo will demonstrate his influence on the impressionist movement, as he was instrumental in organizing its success. He was definitely the victor in the hostilities.” Bernard smooths over what was a very contentious relationship between Van Gogh and the Impressionists, personally and artistically. Van Gogh was aware of the commercial potential of the Impressionists to help Theo’s gallery but, in general, he was quick to see problems with the paintings themselves. And no one can rule out jealousy.

The preface is at its most valuable when it shifts to Bernard’s confident treatise on aesthetics and the nature of beauty. Van Gogh was able to see the sublime, beyond schools or forms. Focusing on that point, Bernard’s preface becomes an essay on the nature of sublimity. “Sublimity entails the union of sound, color, and fragrance to form Harmony. It is the gift of equivalences, affinities, interpenetrations — in short, the gift of vision. Vincent Van Gogh possessed this gift.” Bernard could be seen here as classifying Van Gogh as something of an existentialist (which Van Gogh probably would have liked). “Something ceaselessly demands that we try to prove — to people’s childish brains — the verities that the most solid reasoning cannot print or make understood. That is what art makes us feel, and feeling is perhaps something beyond understanding. . . . Art is not the depiction of that which is. It is the eternal truth hidden within the shifting forms of objects and of beings, of worlds and of gods.”

The third and fourth entries, from 1893 and 1895, are very short and don’t offer much that’s new. Credit for promoting Impressionism is shared with Theo, where it mostly belongs. The biographical summaries are more salacious, pushing the tragic aspects of the final years. Van Gogh is “a man who felt, lived, suffered, and loved far more deeply than his artistic contemporaries.” On the question of why he committed suicide, the intelligent analysis of sublimity in the 1893 preface descends into the lurid language of a bad gothic novel: “Profound mysteries surround these speculations. They belong to the Omnipotent — to the force that IS. Perhaps Vincent could do no more than cast a light among us. He did so — it only remains for us to perceive its glow.”

It’s the final entry, the longer preface to Bernard’s edited volume Letters from Vincent van Gogh to Emile Bernard from 1911, that makes this book a worthwhile and engaging read for admirers of both Van Gogh and Bernard. At this point, Bernard has matured enormously as an artist, a theorist, and as a professional writer. Later in his career, Bernard became a prolific art critic and poet; he founded and edited the journal La Rénovation esthétique. Passages such as these retain their illuminating power: “The colors that he named so often, reciting the prism like a litany, were like a mystical rosary adorned with jewels, or waterdrops starring the muddy ground after the storm.” Bernard is finally doing what only he can do — share his personal knowledge of Van Gogh. “Vincent expended himself freely, experiencing the exaltation of ten fervently lived lives. He overstimulated himself in every way possible to achieve these sensations.”

Bernard is wrong about Gauguin and his role in the ear-cutting incident, but he writes sympathetically, even poetically, about Van Gogh’s mental illness:

I understand how much the incompleteness of his work, marked by so much unquestionable genius, demands indulgence and forgiveness. You have to comprehend the impatience of a being who sees the paradise of spiritual equilibrium before him, and who fears he will be denied entrance because the gates are only halfway open. An angel grasping a double-edged sword seems to be always threatening to close them pitilessly to his gaze and footsteps.

The key to Bernard’s appreciation of Van Gogh’s art is his empathy for the man’s sensitive, troubled, and forceful consciousness. His advice remains valuable today.

Matters of technique concerned him less now. He painted better because he was no longer fixated on ranges of color, instead following his private vision. His mysticism inclined him toward a sense of compassion that drew him to suffering fellowmen, inferiors and the poor, victims of inhumanity, the sick and the lost. Even in depictions of nature, he expressed tenderness for an old tree covered in ivy or an empty fountain in the park, where leaves lie heaped like a faded cloak.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, 1886. Photo: Wiki Common

Bernard is not above a digression to settle some personal scores with Gauguin, accusing the latter of stealing some of Bernard’s ideas and techniques. He considers Van Gogh’s fondest wish of setting up a cooperative of fellow artists. (“By safeguarding their material life, by liking each other as pals instead of getting at each others’ throats, painters would be happier and anyway less ridiculous, less foolish, and less guilty,” Van Gogh wrote). Bernard declares it a doomed idea from the start. Artists are too solitary, and “the cult of individuality has slain unity. . . . Artists reject the concept of unity; they are perplexed by the myriad unwholesome ideas that pervade our consciousness.” It would have been good if Bernard had been able to have this conversation with Van Gogh, possibly to save him so much suffering when the artists’ cooperative in the yellow house in Arles didn’t work out with the deeply egotistical Gauguin. Perhaps Bernard is continuing an unfinished conversation with Van Gogh in the grave.

But Bernard really takes flight with a brief but insightful overview of color theory in art, including how it works with shadow, shape, lighting, and perception. He describes what the Impressionists got wrong about color (while admitting he helped spread the error early on). Van Gogh was able to master and then transcend such debates with a much broader sense of form:

He first concentrated on building a framework of bold lines to discern the fundamental balance of harmonies presented by nature. Then he elaborated the arabesques with his vibrant touches, strokes, dots, and stripes, all intended to give the composition a sense of motion. It was all done by impulse, without cold calculation, with the unerring intuition of a passionate soul, a fervent heart.

Insights like this are only possible from a fellow artist, and a close friend.

The book concludes with six selected letters from Van Gogh to Bernard. The letters are chosen (presumably by Bailey) for what Van Gogh has to say about his own and Bernard’s artwork and aesthetics. Missing are the letters about their volatile friendship, including the key letter where Van Gogh lays into Bernard about his religious art. Such letters are important, at a minimum, for any thorough overview of their relationship. A longer scholarly book that studies the complete Van Gogh/Bernard axis remains to be written.

Still, even in just six letters, you can still sense the full force of Van Gogh. “Isn’t it rather intensity of thought than calmness of touch that we’re looking for?” Van Gogh wrote to Bernard. “That is what he said about his paintings, seeming to justify their intensity and passion in advance,” Bernard responds. “I also apply this sentiment to his letters. You must feel the thought behind them, the genuine life that is expressed there. ‘Calmness of touch’ is certainly not apparent.”

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. You can find an archive of his essays and reviews at allenmichie.medium.com.

No Comment! Be the first one.