She Made Her Way in the Art World

Another early work, a charcoal drawing of one of her students at the Palmer Institute, Negro Youth (1929), won her an honorable mention from the same national competition. In this portrait in profile, the young man’s gaze appears at once determined and wise, as though weighing the odds he must surmount to achieve his dream.

Jones was well-attuned to such a challenge. For a 1941 annual invitation for entries at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., she had a white friend submit her painting for her to conceal the color of her skin. “If I had brought my entry down myself, and the guards had seen me, they would have put it in the reject pile right away,” she told her biographer Benjamin.

That oil-on-canvas landscape painting, Indian Shops, Gay Head, Massachusetts (1940), won the prestigious Robert Woods Bliss prize for landscape painting. She had to accept the award by mail to again conceal her identity—the Corcoran refused to accept submissions by Black artists. A half century later, the Corcoran held a retrospective exhibit of her work, and apologized for its past discrimination.

Facing the African Diaspora

Jones’ career can be divided into three distinct phases that address the African diaspora, says Martina Tanga, curatorial research and interpretation associate at the MFA Boston. Jones’ work in the 1930s is primarily cityscapes, still lives, and portraits rendered “in a Western style, even though some of her subject matter is not Western,” Tanga says.

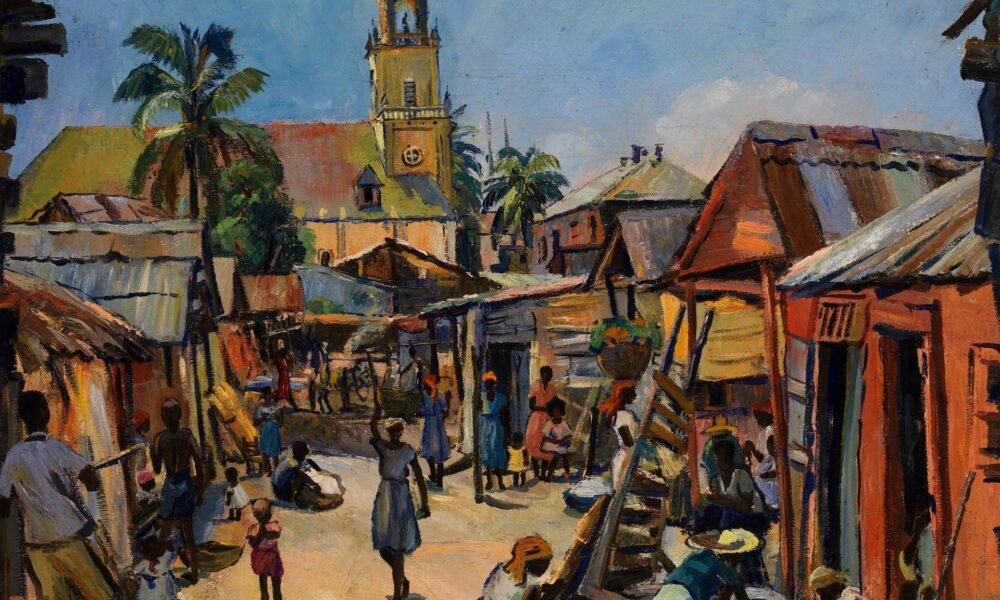

In the 1950s and 1960s, Jones traveled regularly to Haiti, where her husband’s family lived. During that time, her palette became brighter and more intensely colorful, and she began to incorporate the decorative patterns and African-influenced styles she found there. Then, in the 1970s, she visited Africa to engage with contemporary artists and learn about cultural traditions.

Loïs Mailou Jones, “Initiation, Liberia,” 1983, acrylic on canvas, 35 1⁄4 x 23 1⁄4 in. (89.6 x 59.1 cm).

Image: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of the artist, 2006.24.7

In this last phase, she “shifted from a Western renaissance perspective of looking at the world to something that is more diagrammatic.” While still employing Western techniques, Tanga notes, she returned to “the cleanliness of mind and geometric patterning” of her early work in textile design.

One example in the MFA collection is the acrylic-on-canvas painting Ubi Girl from Tai Region (1970). The face of a young woman—her forehead and cheeks painted in white and a crisscross of red lines—floats above a dark mask in profile and iconography from Côte d’Ivoire, which Jones visited.

“In this painting, Jones sees the girl as connected to the strong women in her extended family, past and present,” Tanga explains. “Jones may have felt a kinship to this girl as she considered her relationship to ancestral Africa and the women who linked her to this land.”

Her Home in Art History

Over the years, the accolades kept coming, increasingly with the full recognition of the artist as well as her artwork. She received honorary doctorates from several schools, including Howard University, and the White House honor from President Carter in 1980.

Her paintings are now part of the permanent collections at many museums and galleries, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Phillips Collection, the National Museum of American Art, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, as well as numerous works that span her career over the 20th century at the MFA Boston.

In many ways, Jones has indeed made Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts her home. In 1972, the MFA honored Jones with its first solo show by a Black woman and has since featured her work in other shows. During the four decades since her graduation from the SMFA, she returned multiple times for studio visits with students, often on her way to Martha’s Vineyard, where she maintained a studio throughout her life.

“Mentoring was very important to her practice as an artist,” says Tanga. “Her impact on Boston artists was huge.”

Rob Phelps is a freelance writer based in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

No Comment! Be the first one.