The Art of Senga Nengudi Invites Us to Find Beauty in Everyday

Richard Serra, “Torqued Ellipses,” 2003-2004. 14′ x 27′ 3″ x 29′ (4.27 x 8.31 x 8.84 m); plate thickness: 2″ (5 cm). (Courtesy: Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, Dia Beacon Foundation, © 2023 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York).

Richard Serra’s four “Torqued Ellipses.” Louise Bourgeois’s “Crouching Spider.” Dan Flavin’s neon fluorescent light sculptures. These are the works of art that, based on my occasional explorations of social media at least, most people make a beeline for when they visit Dia Beacon, the popular museum in upstate New York devoted to modern and contemporary art. In sheer size and scale, those works are certainly impressive. But there’s so much more to take in. Currently, there’s also Melvin Edwards’s forbidding yet strangely beautiful barbed-wire sculptures, Robert Smithson’s gnarly “Map of Broken Glass,” and Larry Bell’s rapturously airy use of glass in “Duo Nesting Boxes,” “Standing Walls I,” and more. (For those who have less Andy Warhol fatigue than I do, Dia Beacon is also exhibiting his multi-canvas 1978-9 epic “Shadows.”)

On a recent visit to the museum, though, the works that really caught my eye were those of an artist whose name I had not heard before—African American artist Senga Nengudi. Not that she is new to the art scene. According to the museum’s informational card, Nengudi has been active since the mid-1960s in both the fine arts and dance, having majored in the former and minored in the latter as an undergraduate at California State University, Los Angeles. She is hardly a household name, however, but her works, which have been on display since last February, are striking enough to suggest that she ought to be.

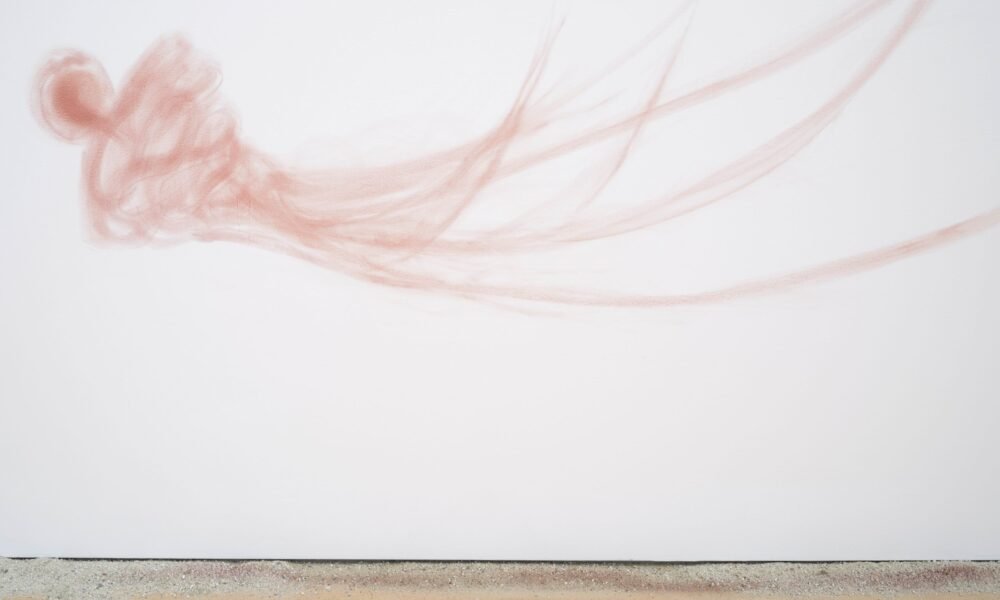

Senga Nengudi, “Wet Night—Early Dawn—Scat Chant—Pilgrim’s Song,” 1996. Earth pigment on wall, spray-paint on cardboard, dry-cleaning bags, bubble wrap, and mixed media. (Photo: Thomas Barratt).

What immediately struck me about Nengudi’s work was its multicultural feel. One gets a sense of that with “Wet Night—Early Dawn—Scat Chant—Pilgrim’s Song,” the first big-scale installation one will encounter upon entering the section of galleries that house her work. On each of the four walls is a painting featuring a pattern or image spray-painted on cardboard draped with dry-cleaning bags and bubble wrap, with translucent earth-pigmented images of abstract figures in flight painted on the otherwise white walls. The use of earth and found elements suggests Native American influences, but the spare interplay between red and white on the walls also invokes Japanese sources. That’s fitting for an artist who spent her formative years in the ’60s in Japan, drawing on ideas explored by the Gutai Art Association, a collective that tried to reconcile modernized present and ancient tradition in their visual and theatrical work.

Senga Nengudi, “Water Composition III,” 1970/2018. Vinyl, water, and rope. (Photo: Thomas Barratt).

Those bags with items inside hanging underneath the paintings in “Wet Night—Early Dawn—Scat Chant—Pilgrim’s Song” are themselves the focus of some of the ‘Water Composition” sculptures featured in another gallery. These assemblages of bright-colored water locked into clear vinyl bags hanging from a rope or tied down to the floor were some of her earliest works, and they’re still as strange and startling now as they surely were then. Less immediately eye-catching but similarly scintillating is a more recent Untitled work from 2023 that uses earth pigment, strings, and pins to create what could be seen as her own take on the American flag, except with red circles within squares instead of red and white stripes, and shorn of a blue square with 50 stars on it. Maybe one could read some kind of political intent into it, but as with all of Nengudi’s work, it stands above easy ideological pigeonholing.

Senga Nengudi, “Sandmining B,” 2020. Sand, pigment, steel, nylon mesh, and digital sound file. (Photo: Thomas Barratt).

The pièce de résistance of Dia Beacon’s Nengudi showcase, however, is her majestic 2020 installation Sandmining B, which, in this context, feels like a summation and expansion of her visual motifs. The twisty steel sculpture at the center of the back wall of the gallery is offset by a kind of shimmering rainbow halo of earth pigments, all of which jump off the white walls like quiet fireworks. Most enchanting, however, on the ground is a large hill of sand featuring not only bits of swirly steel pipe popping up but also little mounds with colored peaks with smaller wire sculptures behind many of them. The installation as a whole put me in the frame of mind of a Zen garden, albeit one refracted through the perspective of an artist who is not so much trying to create a sanctuary from the world but trying to work some of those elements into an inclusive mishmash. There’s beauty to be found in the everyday, Nengudi’s work as a whole suggests, if we open ourselves up to it.

No Comment! Be the first one.