The art market is showing signs of revival — but experts urge caution

The art market staged a comeback this year, but while sales are up on a dismal 2024, sustaining business in nervous times remains insecure.

The welcome news is that, as of December 12, auction sales at the leading firms of Christie’s, Phillips and Sotheby’s were up a combined 15 per cent year-on-year, according to the data analytics firm Pi-eX. The results mark the sector’s first annual gain since 2022.

Improvement was heavily weighted in the second half of the year, a less volatile macroeconomic period, which helped auction sales gain 38 per cent on the previous year, following a first half fall of 7 per cent.

Bonnie Brennan, CEO of Christie’s, says that “stability in financial markets always gives collectors permission to focus on what we are doing and gives consignors confidence to sell”. Her business projects total sales of $6.2bn for the year, up 6 per cent.

Christine Bourron, CEO of Pi-eX, urges caution nonetheless. “Although these positive results will undoubtedly inject renewed confidence and optimism for 2026, further evidence is required to confirm that the public auction market has entered a phase of sustained recovery.”

The broad numbers certainly mask many variations. The market is undergoing a broadening of taste, away from the fine art beloved by previous generations and towards areas such as design, jewellery and cars, where establishing value is less mysterious to newcomers. These include younger buyers and those from the art market’s latest target countries in the Middle East. Christie’s reports its female collector base grew 10 per cent this year.

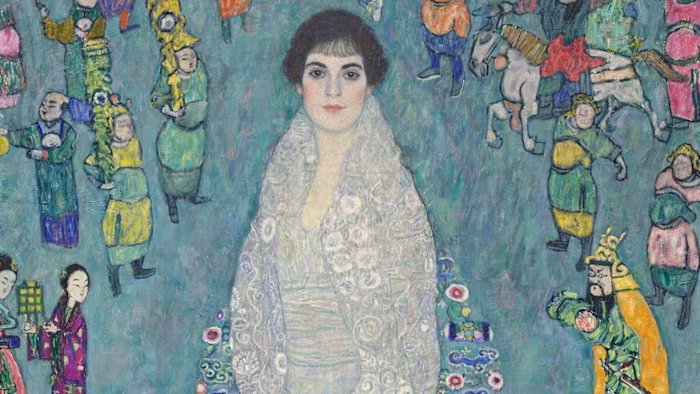

And while $10mn-plus, and even $100mn-plus public sales might be back — notably Gustav Klimt’s enticing “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer” (1914-16), which sold for the year’s highest auction price of $236.4mn — not all fine art is in vogue. In the same Sotheby’s evening session last month, a painting of a Black couple admiring a seaside sunset by the American painter Kerry James Marshall, estimated between $10mn and $15mn, went unsold.

The work had the makings of a hit — the artist holds the auction record for a living African American artist ($21.1mn, made in 2018) and is currently the subject of a major solo show at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. Yet its price seemed too steep in today’s cautious environment.

Meanwhile, auction numbers tell, at best, half the story as the numbers do not incorporate gallery sales, which are not public. And within the gallery sector, results again are mixed. “It’s not a straightforward picture,” says Jo Stella-Sawicka, a partner at Goodman Gallery.

Despite a number of high-end sales reported from art fairs this year, Stella-Sawicka notes that “lots of galleries are relying on their secondary market sales at the moment,” namely the reselling of work generally by established 20th-century artists.

This can bring in some big numbers. At Art Basel Paris in October, Hauser & Wirth reported a $23mn Gerhard Richter abstract from 1987 while Pace sold a 1918 portrait of a young woman by Amedeo Modigliani for nearly $10mn. But the shift illustrates a new mindset, as buyers seem to have lost faith in the fundamentals of newer art as an investment, stretched beyond reality in recent years.

“There’s definitely a natural pivot in the cycle. Everything gets overbaked, so everyone loses faith in the market for a while and when it begins to return, everyone wants to buy [relatively safe] Picassos,” says Marc Glimcher, CEO of Pace.

He has recently formed a new secondary market business, joining forces with the dealer Emmanuel di Donna and with David Schrader, previously chairman of private sales at Sotheby’s, partly to address what Glimcher sees as “a more intense time, because the speculation in younger artists was itself so intense”. He characterises the economic backdrop as “we are at the top of an inflationary cycle, which doesn’t mean that the cost of doing business comes down, it just stops going up.”

Margins are being eroded elsewhere. Galleries take about a 10 per cent cut on secondary market sales whereas the takings for new work, made by the living artists that they promote (the primary market), are nearer 50 per cent.

Meanwhile, to help win business, the auction houses have stepped up their so-called “guarantees” — where they commit to a minimum price for a work, regardless of whether or not it sells — and “third-party guarantees”, a mechanism through which they pass on this risk to another buyer, who may not eventually win out at the live sale, but who gets a cut either way.

Charles Stewart, CEO of Sotheby’s, says “it is all very manageable in the context of $7bn of sales [their projected turnover this year, up 17 per cent].” He adds that “as the financialisation of the art market creeps forward, giving our consignors and buyers access to capital is relevant”, such as through loans and their guarantee arrangements. Expenses-wise, he says, “we run a tight ship. You have to manage all costs very closely to make the business work. But I suspect that is true in most, if not all, of the 281 years Sotheby’s has been in business.”

Some of the market’s mixed messages played out at the recent Art Basel Miami Beach art fair. “The mood overall was more upbeat, but it was noticeable how many people were missing, including some leading galleries and collectors from all over,” says Nick Campbell, founder of Campbell Art Advisory. “The question is why, and from what I heard, people are exhausted by all this [art market activity]. It has been a long year for everybody,” he says. He describes the latest confidence boost as “a false sense of security”.

The art market has not given up on its primary business, but its intermediaries acknowledge that pricing needs to be conservative and that taste is no longer in favour of the challenging, bright young things. Stella-Sawicka reports sales between £90,000 and £300,000 from Goodman’s ongoing London show of the 78-year-old British-Caribbean painter Winston Branch and says that “museums and private collectors are engaged with historically significant figures.”

Glimcher says that “this isn’t the [early] 1990s, when the primary market stopped.” He gives the example of Loie Hollowell, an American painter of pulsing, biomorphic forms: “We still have waiting lists. But where these were maybe 25 [people] for each painting, now it’s more like eight. But that still means every painting gets sold,” he says.

In the immediate term, Glimcher believes there are opportunities, stemming from the artists themselves and, for their intermediaries, through strategic consolidation with other art businesses and in technology. “There is a wave of authoritarianism and machine-based creation happening at the same time. I’m pretty sure I saw that movie, and it’s scary,” he says. “It’s all changing, and we’d better be ready for it.”

No Comment! Be the first one.