The Gaza artist who left on October 6, traumatised by survivor’s guilt | Features

On October 6, Malak Mattar packed her suitcase at her family home in the Gaza Strip, in the Remal neighbourhood.

It’s an area near Gaza City that has been since reduced to rubbly by Israel’s war.

Armed with a degree from Istanbul Aydin University and a creative residency visa for the UK, 24-year-old Mattar was on her way to London to start a Master’s degree in Fine Art at the renowned Central St Martin’s college.

She hugged her mother, younger brother, and sister goodbye. Her father drove her to the Civil Affairs bus stop, where she boarded a bus to the Beit Hanoon (Erez) crossing, before heading to Amman, Jordan.

She caught a flight to London, just hours before war was to ravage her homeland again.

Mattar was excited thinking about her student ID at her new college.

But joy soon drained out of her life as she heard the news.

“I have no words to describe that day, and for what followed. I still find it hard to take myself back to that time,” she said, referring to October 7.

Israel launched a fresh assault on Gaza soon after Hamas, the group which governs the Strip, attacked southern Israel on October 7. On that day, 1,139 people were killed and more than 200 Israelis taken captive. Since then, about 34,000 Palestinians have been killed, mostly women and children, raising alarm about Israel’s military conduct across the world.

Born and raised in Gaza and having lived through four wars, Mattar said she knew Israel’s latest onslaught would be different from the rest.

“2014 is the war that we would all talk about. A 51-day lockdown. Death and destruction. But I could tell this was going to be worse … I just never thought it would become a genocide.”

In those first few months of the war, she felt “paralysed”.

The hand of fate had may have saved her by just one day from “being trapped in hell”, but she was consumed with worry, not knowing whether her family – her parents and at least 100 other relatives – were alive or dead.

“Everything just felt meaningless,” she said.

“After each air strike there would be power cuts and communication would go down. Sometimes it would be a couple of hours before I could get through to them, other times days, and then weeks.”

Glued to the news, her days and nights turned into one, as she watched “the atrocities and massacres committed every single day to my people and homeland”.

Painting genocide

In time, she realised, making art during the “genocide” was so important.

“If not now, then when?” she said.

“It’s just as I learned about the Nakba through the work of Sliman Mansour and Tamam Al Akhal, I could experience how the artists felt through their work, and I’m hoping my work will add the same value.”

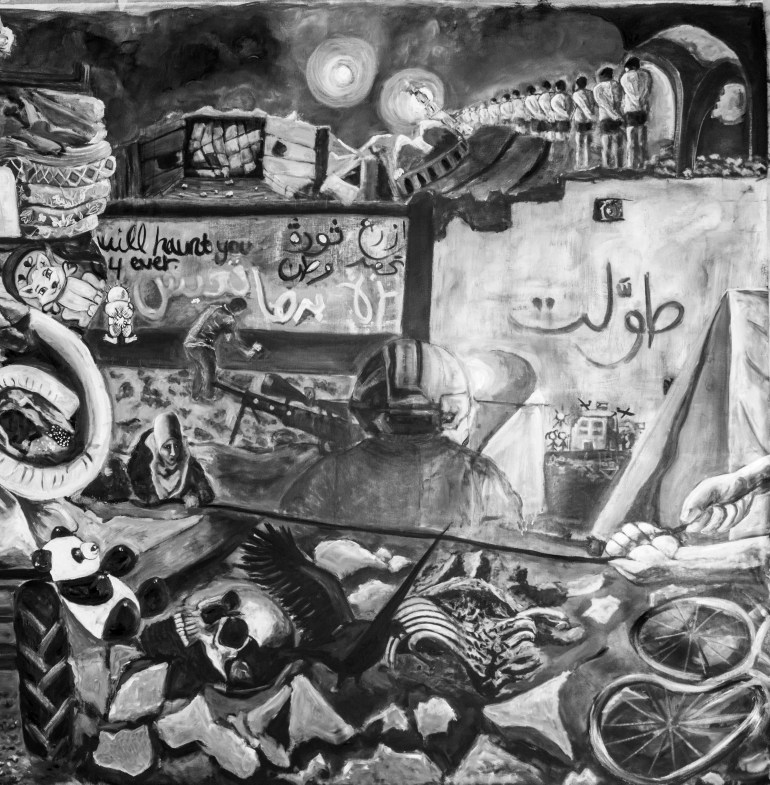

No Words is Mattar’s largest painting yet, at about 7 feet tall and almost 15 feet wide.

When opening a box of paints, she discovered that the rainbow of colour that once brought life to her iconic pieces now served no purpose.

“The world drained my colours.”

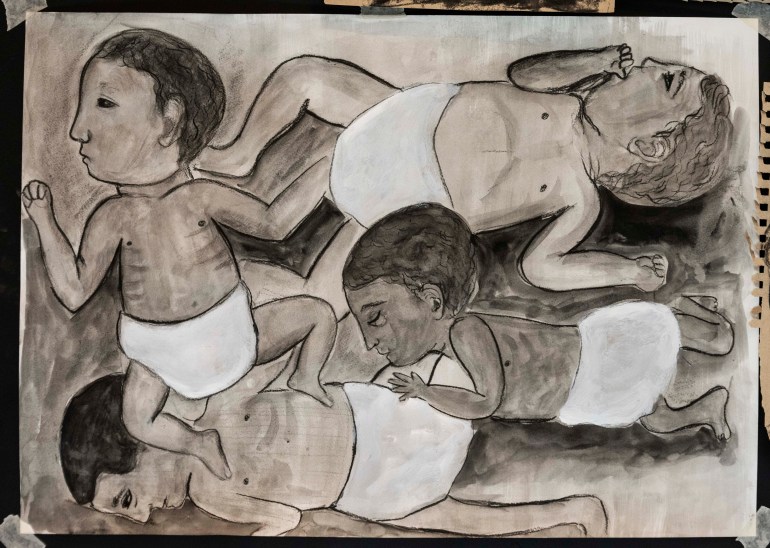

Now her canvases are filled with sombre shades of black, white and grey, like the images of a destroyed Gaza that haunt the news.

“If it’s uncomfortable to look at, that’s good. Don’t get comfortable. This is reality, there’s a genocide going on. This isn’t a TV screen that can be switched off.”

Painting was painful, rather than cathartic, she said.

Malak said she had heard of survivor’s guilt and dismissed it as a “fancy English term”, but now understands its meaning.

“There are no words to describe it, knowing you’ve survived, but all your loved ones are living through it, and many won’t make it. It’s horrific pain.”

Drawing from witness testimonies and images from family and friends, the news and social media, Mattar painted for a month from January to February.

Broken toys, press jackets, hollowed eyes, skeletal children, body bags and rolled mattresses of the displaced featured in her work, as well as Handala, a cartoon character by the late Palestinian artist Naji al-Ali, who was gunned down in London in 1987.

Palestinian artists who narrate their struggles and raise awareness through their work are vitally important, said Dyala Nusseibeh, an art director working with Middle Eastern artists.

Nusseibeh is also one of the organisers of Mattar’s new exhibition, which is titled The Horse Fell off the Poem after Mahmoud Darwish’s eponymous poem.

No Words and more of Mattar’s paintings are on display at the Ferruzzi Gallery in Italy’s Dorsoduro, running alongside the 60th Venice Biennale.

The theme of the Biennale is Stranieri Ovunque, or Foreigners Everywhere, as proposed by the event’s curator Adriano Pedrosa.

“Pedrosa’s premise is that space must be made for the work of indigenous people, for those displaced or forcibly out of place, to be brought into the centre,” said Nusseibeh. “Malak’s works respond immediately and urgently to this call. It is important that her work is seen and that her voice, as one of the most promising artists of her generation, is heard.”

But Palestine has never had a pavilion at the prestigious art event because Italy doesn’t recognise it as a sovereign state. It has participated on the sidelines twice before, once in 2022 and before in 2009.

This year, a collateral Biennale event in Dorsoduro, minutes away from Malak’s own exhibition and titled South West Bank, will show works by a group of artists based in or near the southern West Bank in Palestine, further strengthening the presence of Palestinian art at the Biennale.

“Palestinian art is vital because it bears witness, whilst the destruction of culture now under way in Gaza has, at its core, an urge to silence, rupture and brutally erase. Bearing witness is at the heart of Malak’s recent works on view in Venice and is a holding to account,” added Nusseibeh.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, and the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, as of last month, there were 45 writers, artists and cultural heritage activists killed since the start of the October 7 war.

Heba Zagout was among them, an artist painting Palestinian landscape and iconic architecture, and also muralist Mohammed Sami Qariqa.

The Venice Biennale has been beset by controversy this year, as Israel’s war in Gaza rages on.

Mattar was among the almost 24,000 prominent artists and cultural workers who signed an open letter demanding Israel’s exclusion. Cultural boycotts of the past include a ban on South Africa during the apartheid years and more recently, Russia’s exclusion amid its war on Ukraine.

The calls were rejected by Biennale organisers.

Italy’s culture minister, Gennaro Sangiuliano, released a statement, expressing his support for Israel.

“Israel not only has the right to express its art, but it has the duty to bear witness to its people precisely at a time like this when it has been ruthlessly struck by merciless terrorists,” he said.

The Israeli pavillion is shut, however. An dissenting artist representing Israel has refused to open it until a ceasefire is reached.

While Mattar’s family has recently evacuated from Gaza, she wants her work to serve as a reminder.

“It’s not happening in some far-off world, it’s happening in a world we all live in. Wake up. Gaza is just over four hours from London, it’s three from Venice.”

No Comment! Be the first one.