Jane Rosenberg, sketch artist of the condemned: ‘We love to see the rich and famous fall’ | Culture

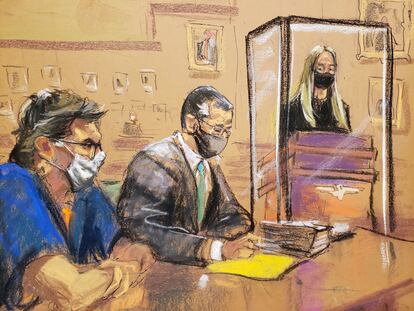

Donald Trump, Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, Mick Jagger, Martha Stewart, Woody Allen, John Lennon’s killer… Jane Rosenberg has drawn them all.

The United States bans cameras, phones and electronic devices from federal courts. And that’s where the sketch artist’s magic comes in. Racing against the clock, she sits in the front row of the audience, pulls out her wooden easel and stains her hands with her pastel palette to capture the verdict of a jury, the anguished faces of the accused, or the moments that will forever change the lives of the protagonists of her works. Sometimes, she has time to capture several different scenes. However, other works must be completed in less than 10 minutes.

After 44 years as a witness to the highest and lowest of human passions, Rosenberg has published Drawn Testimony, a book that contains the most important cases she’s worked on. “I love drawing people,” she says, in her interview with EL PAÍS. “I was always an artist, but for years, I was a starving artist. I drew on the sidewalk with a little hat out and did what I could to earn money, but it was very difficult.” One day, in the early-1980s, she went to a talk given by a court reporter and fell in love with that world.

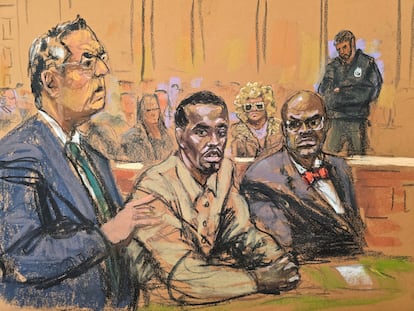

Soon after, she received her first big opportunity: to portray the man who shot John Lennon. “I knew nothing about law and, when I saw his lawyer, I hated him. How could he defend this murderer?” she remembers. Rosenberg immersed herself so much in the world of criminal trials that she ended up married to a litigator. Four decades later, she hasn’t stopped working or painting for pleasure. “I thought I would have a little free time, but then they arrested [New York City Mayor] Eric Adams, they arrested P. Diddy,” she sighs, while discussing her daily life. “Things keep happening.”

Question. What things does an artist see that a reporter can’t see?

Answer. I focus a lot on making my sketches look like the people I draw and [depict] their emotions. I always try to capture emotions: if they look worried, or if they’re full of tears, and take out a handkerchief. That’s the first thing. I guess it’s the same thing a reporter looks for. We can both be seeing the same thing… only you don’t worry about the composition, but about the pieces you have to write. I tell the same story, but with an image. I try to help journalists: I’m a supplement to the story that’s being told in written words.

Q. What has been the most difficult case to draw?

A. All cases are complicated and challenging. If my job were easy, I would quit. It would be very boring. I love what I do; every day, I face a new challenge. Every time I go into court, I get nervous, I think about what I’m going to draw, I look everywhere, I get very stressed… and, actually, I love it. If I didn’t, why would I still be working? I’ve been old enough to retire for years, you know? I can’t pick one case. The most interesting case is always the one I’m working on that day.

Q. Sometimes you have to cover horrific trials, about terrorism, murder, pedophilia… doesn’t that affect your work?

A. Early on, I worked on several cases that made me cry. I remember being at the trial of Susan Smith, a mother who drowned her two children. I was staying in a hotel that was far away [from home] and I had a son of about the same age [as her kids]. I had to listen to testimony about what happens to a person’s brain when they’re drowned. I started to cry… but I had to be very careful not to let the tears ruin the drawing. I’ve had to learn to control my emotions. I feel things, but I try not to cry on the paper. My job is to capture other people’s emotions and what’s happening — not what I feel.

Q. Trials are horrible times for the people who are part of them, but they become fascinating for the public. Why do you think this happens?

A. People love to see the rich and famous fall from grace. It’s a topic that the media loves too. And they send me where they want me to go: “Can you cover this?” Sometimes it’s powerful people, rich people, or well-known people, sometimes it’s not big shots. Look at Diddy. He was living the high life, he controlled everyone… and now he’s sitting in a courtroom in a prison uniform. His life has changed completely. I don’t know, maybe people are interested in seeing that no one is above the law; that other people’s lives aren’t so perfect, that nothing is what it seems.

JANE ROSENBERG

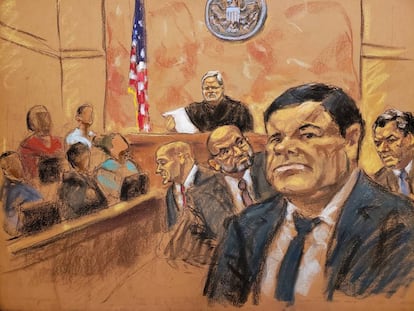

Q. What was it like drawing El Chapo?

A. It was an extremely difficult case because of all the security. I would arrive at court at 2 a.m. It was, like, minus 13 degrees. People would camp outside to get in and it was very important for me to sit in a good spot. I was lucky that El Chapo’s wife often sat behind me. So, he would look at her a lot and always blow kisses to her. That helped me, because I could see him in the front row, although it was like he was blowing kisses to me!

Q. Wasn’t that weird?

A. A little bit… he didn’t look like these super powerful guys. He was a short man with bright eyes. He wasn’t like how I imagined him. But people don’t always look the part they play. Bernie Madoff stole a lot of people’s savings, but you saw him and he looked like a nice old man. Many people gave him their money because he had a face they thought they could trust. People don’t always look like what they really are. I’ve learned that from drawing other people.

Q. And Trump?

A. Trump does look like what he is. Grumpy, upset. That is, when his eyes are open. Because at the trial, he closed them a lot.

Q. Some people think that the artist draws them badly when they don’t like them. Does that happen?

A. No, it doesn’t. People think I’m editorializing or drawing my opinion of a person. It’s not about that. [During the Trump trial], I drew him every way I saw him: smiling, looking grumpy, eyes closed and open, arms crossed, yawning, talking to his kids… whatever he was doing and whatever was going on. It’s not about me deciding what’s my opinion of Trump, or of anyone else.

Q. Are there any drawings of yours that you don’t like?

A. There are some that I’m embarrassed about. Many. Sometimes, when a lot of people see them, I feel very embarrassed. I have to just, like, close my eyes and hope I get another assignment the next day. I have to work extremely fast, with extremely short deadlines. I don’t have time to be perfect — only to do the best I can. It’s a hard job.

Q. People can be very harsh. How do you deal with that?

A. I don’t use social media, because that’s where they love to criticize artists. I learned that during the Tom Brady case. I didn’t know who he was — I don’t even like American football. I must be the only American who doesn’t know anything about that sport. When I left the courtroom, I saw a bunch of lawyers looking at my drawing on Twitter. I didn’t even know what Twitter was. I went over to the CBS van and asked them what was going on. They said: “You’ve gone viral.” And then, there were the memes. I didn’t know what a meme was. I came home and had 700 emails. [Brady’s] fans were furious and it was a very hard time for me. I don’t like being the center of attention. I’m a person who sits in the back of the room drawing and I’m happy when my work is used. Sometimes, I get positive feedback… but hardly anyone comments on my art or thanks me for it.

Q. What would you like people to take away from your book?

A. I just hope that they understand what it means to be a courtroom sketch artist. I think a lot of people are curious about my job. They sit behind me and say, “Wow, that’s interesting.” When the day at court gets boring, usually the most interesting thing is to see how the artist works. Art is different from photography: it comes more from the soul, it has more layers. It’s not a set number of pixels. There are people who really appreciate art and I hope they appreciate my work as well.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

No Comment! Be the first one.