Interview: Maggie Lemak On the Appeal of the Art Novel

Over the past few years, the publisher Bond & Grace has come to be known, among a certain set of readers, for its “Art Novels.” This new publishing product merges the worlds of classic literature and contemporary art, resulting in a coffee table-sized product that doesn’t illustrate the story so much as respond to it. The company has just released its edition of The Great Gatsby—in many ways the perfect novel for the end of the summer—and we caught up with creative director Maggie Lemak to hear more about how the project came together.

Before we get into The Great Gatsby, tell me a little more about Bond & Grace’s concept of the Art Novel. What’s the pitch, and what are its advantages over traditional book formats?

Technically speaking, “the Art Novel is a classic text fashioned into a unique, oversized reading experience that pairs classic literature with contemporary insight. It is an illuminating glimpse into the brilliant minds of today’s thought leaders, literary scholars and fine artists—embedding contemporary context, literary analysis, and bespoke fine art within the original text of a classic novel.”

But the secret’s out that when I’m speaking to other artists or giving an elevator pitch to strangers, I lead with, “the Art Novel is an art exhibit in your lap.” It’s the part that excites me most, because, as a painter myself, I know it’s what artists have been yearning for—a conduit for understanding that is metaphorically sponsored by classic literature. In a way, it’s a direct line for anybody to be able to understand the sport of fine art.

This is by design too, as part of our developing the Art Novel as a product—and designing the book’s preliminary layouts—we ensured artists’ voices were at the table, not just on the walls. I called on my fascination with exhibit design and recommended including “collections” of 3-6 artworks from each artist within a cohort of 10-15 artists. The goal was to offer our artists enough latitude to respond to the text fully. I utilized my background as an artist and designer to inform and shape our Artist Experience curriculum, which centered on critique and concept evolution alongside a deep study of the text. Our process is aligned with the kind of concept development more common in “design” work, and in turn, it offers our artists the opportunity to collaborate 1:1 with me and also with our team of scholars in order to refine their first idea in search of the strongest one. From a curator’s perspective, this process allows for some critical logistics—the mitigation of overlapping concepts, foresight into how the collection is evolving, and an opportunity to ensure we have both a diverse array of messages, mediums and subject matter that spans the entire text and is also compositionally strong.

It’s a science, a dance and a puzzle that I absolutely love. Why? Because it’s worth it tenfold to allow artists to be intuitive. Pigeonholing artists into a “commission” or “assignment” won’t create the same quality of work as letting artists be themselves, and I think that perhaps other companies aren’t willing to rearrange their process or develop contracts to make this possible. That’s what’s different about us—we center creativity and thoughtful touches and encourage artists to value their work. In turn, our artists have shared that it was both stimulating and rewarding to work with us, with some going as far as to say that our collaboration, critiques and creative mentorship have inspired them to evolve the way they approach their creative process. It’s been an honor to be able to conduct our orchestra of global talent, and I believe our artist experience is key to the magic we create, even if it’s only the beginning of the Art Novel process.

I believe strongly in our product because it was made for art. The Art Novel is unique in that it provides branches for both artists and art appreciators to better understand one another… and to better understand the text as a bridge between them. It is a far more approachable, gradual and even palatable way to understand the deeper meaning of art than your typical gallery experience.

The best way I can describe it is through this analogy: Imagine that everyone walking into the opening night of your solo show has already read and studied the most lengthy reference for your work. They’re primed to start hearing your thesis and to connect with it in a way that artists can only dream of. That’s the Art Novel. You don’t have to explain what a theme is about, and you can instead dive straight into more complicated dissections or distinct reinventions of those original themes.

Other book formats also cannot compare because they either lack the depth or the breadth of stories. Most art books or illustrated novels represent the work of a single artist, but we intentionally offer a curated exhibition in which our artists are presented in the context of a greater theme and in tension with other artists’ perspectives. Our artists present mini collections that stretch the narrative or investigate a theme at different points in the text. These mini collections are then framed by other artists’ work.

In short, the product design work and creative development strategy for the Art Novel is probably a thesis I should write someday, combining my fascination with curation, exhibit design and visual storytelling. For now, the beauty is that whether or not it’s expressly stated, the vision, stories and concepts are out there for anyone daring enough to dig in. P.S. If you want to talk about it, I’d cry happy tears.

What makes the team decide a certain book is worthy of an Art Novel edition? What’s been your favorite past one and why?

Classic literature being firmly planted in the zeitgeist is what makes our books and the art produced for our books instant classics. But for a book to be on our shortlist, it requires depth, a bit of controversy, a reflection of the essence of a particular historical time period and finally, it has to have tension with the present moment.

Our Alice and Frankenstein titles have both won design awards (an ADC Merit Award and IPPY Award for Outstanding Design, respectively), which has been exhilarating, particularly for a young design team composed of my colleague Romina Krosnyak and me. Romina says her favorite thing we’ve done is the sticker motif in the Alice in Wonderland Art Novel. A game in itself, the “sticker” cut-out treatment was created for forty-two key objects referenced throughout the Alice stories, and it let us put our semiotics obsession on full display. But if I had to pick, I’d say there’s an originality about Frankenstein that will be hard to top. It was an honor to be able to push the narrative with our strategy for that book by recommending that we take a feminine approach to Frankenstein that the world hadn’t seen just yet. We honored the author, a then 18-year-old Mary Shelley, and also the women in the text with a toile pattern we developed alongside Abby Olsen as a romantic dedication to the (badass) female characters and their stories—particularly Mary Shelley’s story. The toile has since been represented on various products we offer, like twilly scarves and linens. But the entire book, really, has an intense, thorough and thought-out design infrastructure rooted in psychology, color theory and elements of narcissism that I could talk about for hours. (I’m aware of the irony in that sentiment.) The design set the precedent for Art Novels to come by introducing transparent and textured papers that coincided with the text’s use of letter writing as an epistolary novel, as well as revelations within the narrative itself that acted as foreshadowing. We went a little mad, like Victor, which helped us prepare for the mad world of Alice.

At the same time, though, I’d be remiss not to mention that the way we approached our first art collection for The Secret Garden was very romantic in that we gave those artists free rein to direct their art—even if it overlapped with fellow artists’ concepts. It had its own design challenges to ensure each chapter had excitement and that the art wasn’t all about the moment when Mary enters the garden, but there was a depth to their work that still moves me to this day—exploring concepts of lush inner gardens, seasons changing, personal evolution and healing as seeds being planted to bloom later as roses. I’m fortunate that I was able to have my own paintings in that Art Novel!

For The Great Gatsby you’ve partnered with a host of artists. Who are some standouts, and how did you come to decide that their work was right for the project?

When we start developing each collection, we identify both themes and beneficial mediums that might offer synergy with the text. For Gatsby, one of the starting places was a direct comparison of the improvised looseness of jazz—in its lack of inhibition and fluidity of movement—with what we dubbed “a vivid glimpse”—a representation of Nick Carraway’s biased, hyperrealistic vignettes of pointed moments in time.

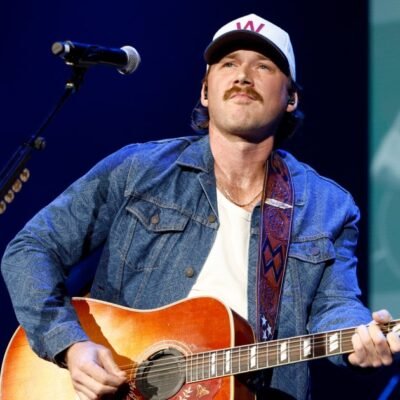

Of course there’s a ton of massaging and development that follows the early conversations with my now co-curator, Annie Lyall Slaughter—who has upped our game by the way—but when we can find an artist who aligns closely with the novel’s themes, with what’s expected of the book from a pop culture standpoint, and with our own succinct abstract for the collection, it becomes a no-brainer. For Gatsby, painters Kevin Sabo and Sheyda Mehrara represented jazz, and hyperrealist Leah Giberson, alongside photographers James Katsipis and Matt Mele, represented our “vivid glimpse” or our varied framings of reality.

The Great Gatsby strikes me as a challenging one, because the external images are glamorous but the story is so dark. How did your artists reconcile those contrary elements?

Well The Great Gatsby was certainly a difficult text because of its relationship to the present day specifically in its mirroring of excess and turmoil, as well as its depiction of wealth disparities, but there was a clarity with Gatsby that we hadn’t felt with previous books. The concept that jumped off the page almost immediately and then became the title of the art collection was “A Vivid Glimpse.”

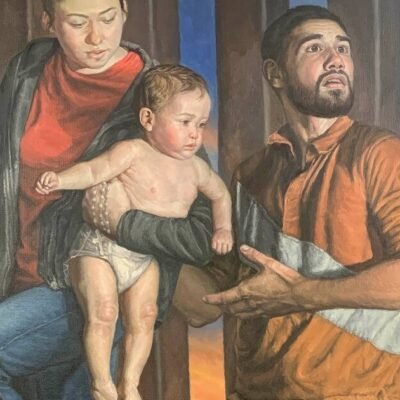

For this text, we encouraged artists to both bask in Fitzgerald’s lyrical writing and also to investigate whether the characters might reflect parts of themselves. I think this prompt helped artists to find humility in the characters and use that humility to go deeper. Several artists pulled from personal experience in order to create their artworks, which always brings a richness to the text that represents the present day in a way that only firsthand narrative can.

The other wonderful thing about creating these worlds through fine art and design is that we get to extend those worlds into the present day through our promotional photoshoots. This offers us the ability to save some of the more expected pop culture elements of these classics for those photos. The development of those photoshoots is actually its own rabbit hole as we draw inspiration from the text, our artists’ interpretations of the text, from the movies as the commoner may know them, and from our strategic creative direction. It’s a fun challenge that always culminates in a set of images with easter eggs abound.

Your edition also features essays by an interdisciplinary and global group of scholars. What kind of context do they bring to the text?

We worked with a fascinating group of scholars who brought lush insights to the text, which Annie Lyall and I use to shape thematic synergy. I think one of the most fascinating topics we discussed—something that an English teacher may not touch on—was a perspective from AJ Odasso, which explored the text from a queer reader’s perspective. Before the research for this project had begun, I was unaware of how Nick Carraway is often read as a suppressed expression of queer identity. Through the scholars’ research, we went on to explore how Fitzgerald had dressed (and posed) in women’s clothing for a play at Princeton and how Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda had, in many ways, ridiculed Fitzgerald’s masculinity when she felt it to be performative. I found this topic particularly rich, and I think that it’s these kinds of deep dives that differentiate our research from annotated novels, particularly in the way that it represents today. Because of their research, we were able to present context to our artists and validate their hunches in ways that support the resulting art. Kevin Sabo offers a great example of an artist whose collection (particularly his paintings Gatsby’s Look and Sweet Fever) explores the scholarship-supported subtext of our novels.

Similarly to what I said before, I do think our books are unique in the way that they position artists as scholars. The vast majority of the artists we work with are creating a mini collection of works in direct response to the novel—a visual time capsule, if you will, that showcases their individual interpretation of the story. Perhaps in 100 years, their firsthand accounts of the world in 2025—as expressed by art and through their artist statements—will be used as research into how a culture—our culture—felt about society at large at this exact moment. That, to me, is what makes our Art Novels robust. We invite artist voices to the table as thought leaders and as people warranted to express the essence of a time as a kind of cultural historian.

As one of our Secret Garden artists, Teresa Bear, once eloquently pointed out, “any major change that has happened in the world involves a photo or some kind of visual showing the world what is happening.” These books are a way to document time and collect these visuals in real time, to present them as an artifact from the start. I think this part of my job is perhaps the most rewarding in that I’m able to solidify that artists’ voices are published as significant parts of what in the future may be referenced as history.

Why do you think The Great Gatsby has endured across so many generations? What is its relevance to today?

This book has endured for 100 years, and I predict it will fascinate generations to come largely because it is both glamorous and haunting. It presents a vision of striving for something that we experience every day in our lives as we pursue our respective dreams—our green lights. Similarly, the book presents a critique of society, so vivid and relatable, that it can be understood almost immediately and intrinsically by anyone who has felt guilt, longing or a desire to be something more. There is not a single person I know who cannot recount a particular summer that seemed to spark a fire within them—and I imagine that fire as their green light.

What I’ve learned from this book is that many of our biggest wants can be distilled down into simpler, beautiful forms, and I think that’s what Fitzgerald has done with this text: take something as complex as wealth disparity and present it as a summer with a sparkling pool, champagne and a manicured lawn. Fitzgerald has brilliantly positioned difficult conversations into the everyday under the guise that they are something that sparkles.

And the crazy part is that it’s just “advertising”—manipulating a consumer until they feel moved to spend. We pulled from this concept of consumerism by presenting a similar subversion in our illustrated inserts for The Great Gatsby Art Novel. We presented advertisements paired with quotes from the book and glamorous “capital beauties,” but if you look a bit closer, they are chock full of warnings about the comorbidities that their existence creates.

Who is your target audience for this project? Are we more likely to see this book under the arm of a Daisy type or a Jordan type?

Our audience for The Great Gatsby Art Novel spans the entire cast of characters. The irony, of course, being that we anticipate many Daisies and Toms will read our book. However, while Daisy and Tom get the most flack, every character has a fatal flaw. This book is as much for Nick, Gatsby and Jordan as it is for Wilson, Myrtle and the mysterious bodies Fitzgerald omits from the text and instead describes as “floating rounds of cocktails.” We can only assume he is referring to Gatsby’s staff, who were, given the time period, probably people of color.

In fact, it has been our duty as we document this moment in time to represent the breadth of identities that were present in the 1920s, that influenced the magnificence of culture and that have the same impact today. A guiding principle for us, from design and content standpoints alike, was that every limelight creates a shadow and every shadow has an equally compelling story to tell.

That said, I think I’m most excited by Daisy, Gatsby and Tom experiencing this title, as they likely have the most means to disrupt the very system that supports their glitz and glamour—to redirect the light beyond themselves.

More in Books

No Comment! Be the first one.