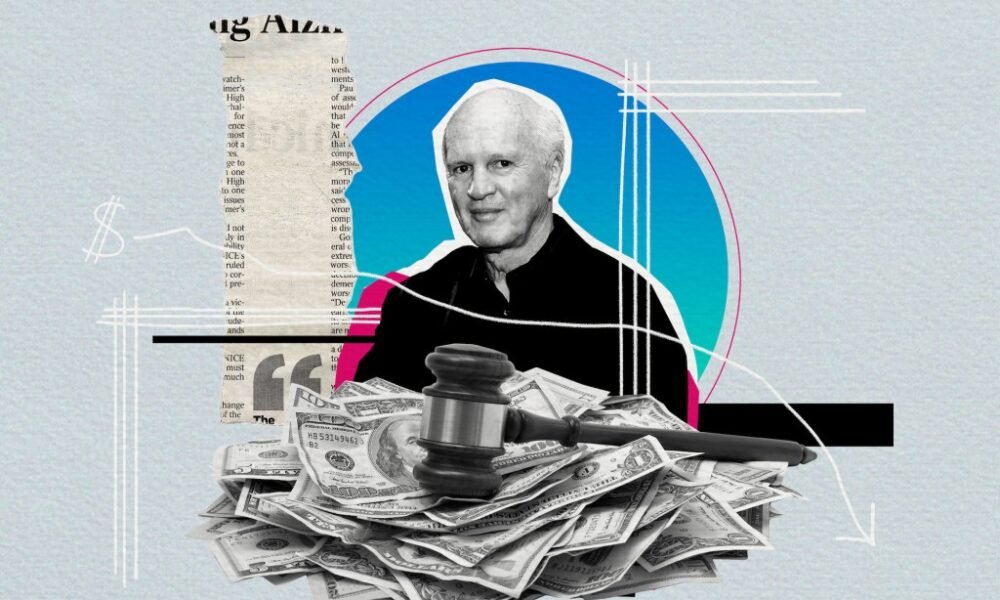

Who Is Doug Chrismas? The Incredible Story Behind L.A. Dealer’s Fall

An Avalanche of Lawsuits

Chrismas was first taken to court in the mid-1970s, when artist Robert Motherwell sued him over the disappearance of nine works, but it was in the mid 1980s that allegations first stuck.

In 1986, Chrismas spent three days in jail on felony grand theft charges. According to the felony complaint, the late Vancouver collector Frederick Stimpson accused Chrismas of losing works totaling $1.2 million that he’d left at Ace for safekeeping. The most expensive piece, Robert Rauschenberg’s Rodeo Palace (1976), Stimpson paid $600,000 for; the other alleged missing works included three more by Rauschenberg, one by Frank Stella, one by Warhol, and an untitled sculpture by Donald Judd. Chrismas had used Rodeo Palace as collateral for a $200,000 bank loan; the bank had seized the artwork.

“The art world kind of keeps these things to themselves,” LAPD detective Dorothy A. Pathe told the L.A. Times at the time, “but I think that when our victim realized that his collection was gone, he didn’t really have any choice but to come to us.”

Stimpson later opted to enter into a payment agreement with the dealer, perpetually delaying sentencing for the next 15 years as Chrismas slowly paid back the collector and then, following his death, his estate. Chrismas refused to say how long it took to pay Stimpson back.

“Regarding Frederick Stimpson, I can say that the family continues to have me sell works from its collection,” the dealer said.

Between 1982 and his stint in jail, Chrismas had filed for bankruptcy three times, under his gallery’s name and his own. None of it seemed to slow his business, and he moved Ace into a beautiful, labyrinthine Art Deco building on Wilshire Boulevard in 1986. In 1994, Chrismas opened a massive 25,000-square-foot gallery on Hudson Street in New York. Then, despite filing for bankruptcy again in 1999, he opened a high-ceilinged, white-walled space in Beverly Hills, blocks from Gagosian, in 2001.

Over the last 30 years, Chrismas has operated ten gallery spaces in North America—in Vancouver and Mexico City, in addition to LA and New York—and has run short-lived spaces in Paris, Berlin, and Beijing. Until late 2016, Ace had three locations in L.A. alone. Chrismas’s prestige, bolstered by the size of his galleries, continued to hold a special allure for major artists, even as the gallerist’s suspect practices were reported in local newspapers and by word of mouth, as multiple artists confirm.

“Ace did things that the County Museum [LACMA] wouldn’t do,” said Light and Space artist Laddie John Dill, who began showing with Ace in the 2010s but has known the dealer for years. Dill cited examples like Ace/Venice’s 1977 exhibition of Michael Heizer’s Displaced/Replaced Mass, which required digging up portions of the floor so that boulders could be dropped deep in the ground.

At the Beverly Hills location, Chrismas staged a retrospective of Sam Francis paintings. When I asked Nicholas, Chrismas’s longtime associate and formerly the executor of Francis’ estate, why he chose to exhibit this work with Chrismas given all he knew, the philanthropist and retired lawyer was blunt: The estate had a huge inventory of unsold paintings that diverged from the style that made Francis famous. Chrismas convinced Nicholas that he could sell every single painting. Chrismas kept his word. “Selling meaningful works of art has never been a problem for me,” the dealer said in a 2022 email. “So yes, the paintings did sell.”

But, by the mid-2000s, Chrismas’s house of cards began to tumble.

Citing the economic ramifications of the 2001 World Trade Center attacks, Chrismas closed the New York gallery in 2005. The following year, artist Keith Sonnier filed a suit against Chrismas and Ace, alleging that he was in “wrongful possession” of 18 artworks by Sonnier collectively valued at $2.83 million. Three months after that, sculptor Jannis Kounellis sued, alleging “improprieties” and the wrongful retaining of profits and consigned artworks worth over $4 million. At the time Kounnellis said Chrismas had been “defrauding artists, clients and art collectors for nearly 30 years,” and he wanted it to stop.

In 2008, Seth Landsberg, an investor who helms a foundation named after himself, sued Chrismas, alleging that he and San Francisco dealer Nancy Wandlass sold him a Lichtenstein painting stolen from the Brazilian government (Wandlass pleaded guilty to a federal embezzlement charge, and received three years of probation). The two dealers had allegedly helped Edemar Cid Feirrera, a Brazilian banker and art collector, smuggle the Lichtenstein and a Basquiat painting into the US using falsified customs documents. Feirrera had been convicted on money laundering and fraud charges in 2006, but when Brazilian authorities seized his assets, they discovered much of his art was missing. Chrismas settled with Landsberg in 2010 for $1.79 million, but as of bankruptcy proceedings in 2013, Ace was still on record for owing over $1.6 million of that money. In 2015, Interpol seized the Lichtenstein and sent it back to Brazil.

In 2011, Ace allegedly pledged 16 artworks—by Rauschenberg, Francis, and Julian Schnabel—as loan collateral. But Ace didn’t own the works – they were owned by Vancouver collector Eric Wilson, Ace’s largest single creditor, who had left the works at the gallery for storage.

Then, in 2012, Vivian and Alan Hassenfeld, philanthropists with a fortune from Hasbro Toys, paid Ace over $160,000 for artworks they never received. Chrismas agreed to repay the Hassenfelds in installments. But, by 2013, Chrismas had defaulted on those payments, just before filing for bankruptcy the final time, according to court documents.

As Sam Leslie and his lawyers have alleged repeatedly, these pre-bankruptcy litigations evidence “a pattern of wrongful behavior” that exacerbated Ace’s financial problems.

Chrismas, as is typical, waved off the bankruptcies and the lawsuits.

“The entire Chapter 11 situation is over one month’s late rent,” Chrismas told me via e-mail in 2016. Hurricane Sandy damaged many Chelsea galleries and brought “the art world to a screeching halt.” The slowdown caused him to fall behind on payments to his landlord and other creditors, he added.

(Chrismas’s own statements to the court acknowledged that problems with payments predated the hurricane, but he attributed these earlier issues to inaccurate charges from his landlord.)

Chrismas also believed his landlord, Associated Estates Realty Corporation (AERC), the corporate owner of Ace’s Wilshire building, wanted to evict him to maximize “its own profits” on a residential housing project. There may be some truth to that statement. When Ace signed the Wilshire lease in 1987, Chrismas negotiated a purchase option for the building and the adjacent lot. AERC did indeed want to build a housing project in the adjacent lot and so, in 2012, it paid Ace $4 million to buy out the option. After receiving that payment, the gallery stopped paying rent and almost all the $4 million was transferred to Ace Museum, Chrismas’s nonprofit, as court documents allege.

Chrismas had also cannily inserted into the lease that the adjacent complex had to be designed by Frank Gehry or some other “acclaimed architect.” He told the court he believed AERC didn’t intend abide by that requirement; AERC said the lease was invalidated due to non-payment. The company eventually used Architect Orange, a firm known for retail centers, to build its nondescript housing complex.

Chrismas is “more a real estate maven than an art dealer,” lawyer Tony Nicholas, Frederick Nicholas’s son, said of the Wilshire debacle.

No Comment! Be the first one.