City Hall may destroy New Orleans’ most beloved artwork | Arts

On a recent afternoon, a yellow backhoe clawed at the base of a long-vacant, five-story apartment building in Algiers as dump trucks waited to haul away the wreckage.

The derelict building slowly being demolished was one of several similar structures in the DeGaulle Manor apartment complex, once home to hundreds of residents.

Called the Bridge Plaza when it opened in 1963, the 15-acre West Bank development cost almost $7 million. Now, the city is spending $2 million to tear it down, eliminating one of New Orleans’ most notorious examples of neglected property, a forbidding urban wilderness of weeds, discarded tires, trash and graffiti.

Ironically, when City Hall eliminates the blighted DeGaulle Manor, it will also destroy New Orleans’ most significant 21st-century artwork.

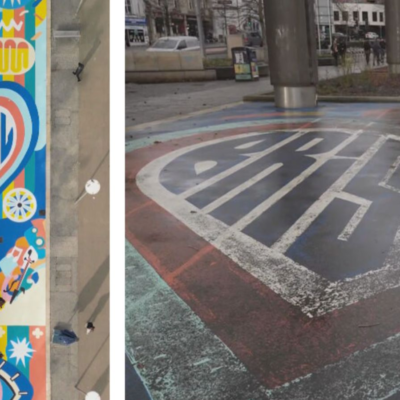

As art-lovers may remember, in 2014 a pack of feral aerosol artists swept into the center courtyard of DeGaulle Manor and created a collaborative painting 60 feet tall and wide enough to span a city block. Thousands of visitors crowded into the ruined apartment complex to behold the colorful, politically pointed artwork and listen to a concert by singer/activist Erykah Badu.

Exhibit BE, as the collaborative artwork is known, was the bygone West Bank landmark’s last hurrah.

An art star in the making

The person behind the art project was a charismatic former NOCCA student named Brandan Odums, who went by the nickname BMIKE. Odums was not a graffiti writer per se. He was an artist, videographer, educator and activist who became aware of the underground graffiti scene taking place in the abandoned and fenced-off Florida public housing development that had been closed after Hurricane Katrina and the 2005 flood.

In 2013, Odums began ducking secretly into the empty apartments, spray-painting huge portraits of Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., Nina Simone, Malcolm X and others.

He had an obvious knack for color and composition. But more importantly, BMIKE understood the importance of context. It seemed poignant and haunting to encounter these Civil Rights heroes in a ruined public housing development where Black families lived before the storm.

The trouble was, there was practically no audience for Odum’s artistic triumph, which he dubbed Project BE.

Exhibit BE

But within a year, Odums was back at it. He’d invited a platoon of muralists to join him in a new project, called Exhibit BE. The new project would be located in the almost forgotten DeGaulle Manor, which had the same forlorn vibe of the Florida apartments. This time the artwork was going to be mostly outdoors where people could see it more easily.

As BMIKE produced a new suite of Black historical icons, the other daredevil artists — some masked to protect their anonymity — scrambled along the open balconies rendering a wild amalgam of images: a gigantic Calvin and Hobbes cartoon, purple dinosaurs, space aliens, a macabre skull, Old Man Winter and a four-story anarchist bomb-thrower.

The effect was a random collision of images and intentions that Odums capped with an enormous portrait of a New Orleans teen who’d recently died of gun violence.

Exhibit BE was a surrealist survey of outstanding graffiti-style muraling, with an underlying theme of social justice that dovetailed with the outrage provoked by the death of Michael Brown at the hands of a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, a few months earlier.

“It was a real amazing moment in New Orleans art culture,” said Ogden Museum of Southern Art curator Bradley Sumrall. Exhibit BE, he said, “was a masterpiece of renegade collaborative urban expressionism” and a “seminal moment for street art in New Orleans.”

The enormous artwork “brought community together, brought international attention to New Orleans as an art destination, and opened dialogue about important social and cultural issues.”

“To use a technical art term,” Sumrall said, “it was just super cool.”

Hotel developer and street art fan Sean Cummings, who’d paid for the paint used to produce Exhibit BE, underwrote a public reception for the gargantuan painting and the closing block party that featured Badu and other stars.

Despite the decidedly gritty location, the site was packed with an appreciative audience. No single 21st-century New Orleans artwork had the impact of Exhibit BE.

Forgotten but not gone

Graffiti is like a bouquet of flowers. Nobody expects it to last very long. But amazingly, a decade after it was created, Exhibit BE still exists, more or less intact, though it has mostly slipped below the radar.

For the past several years, to visit the painting was to trespass in a hazardous area. On Monday, a young urban adventurer wandered the site until he was firmly asked to leave by a construction worker. Asked why he’d come to the forbidding site, he said “to see the work of a Black man being torn down.”

“His art’s pretty cool,” he added.

The worker said he wasn’t sure how long it would be before the three buildings that hold the 2014 artwork would be toppled. But demolition was underway across the street. A small outlying portion of Exhibit BE has already been removed.

Since 2017, DeGaulle Manor has been owned by landlord Josh Bruno through a limited liability corporation. A fire in September 2023 damaged some of the complex, and in November, it appeared on the city’s “Dirty Dozen” list of high-profile blighted properties slated for demolition or rehabilitation.

Neither BMIKE, the Mayor’s Office or district City Councilmember Freddie King immediately replied to requests for comment.

No Comment! Be the first one.