Investing in Fine Art the Securitized Way

I recently purchased an interest in a painting by famed American artist Andy Warhol. But don’t expect to see it hanging in my living room anytime soon.

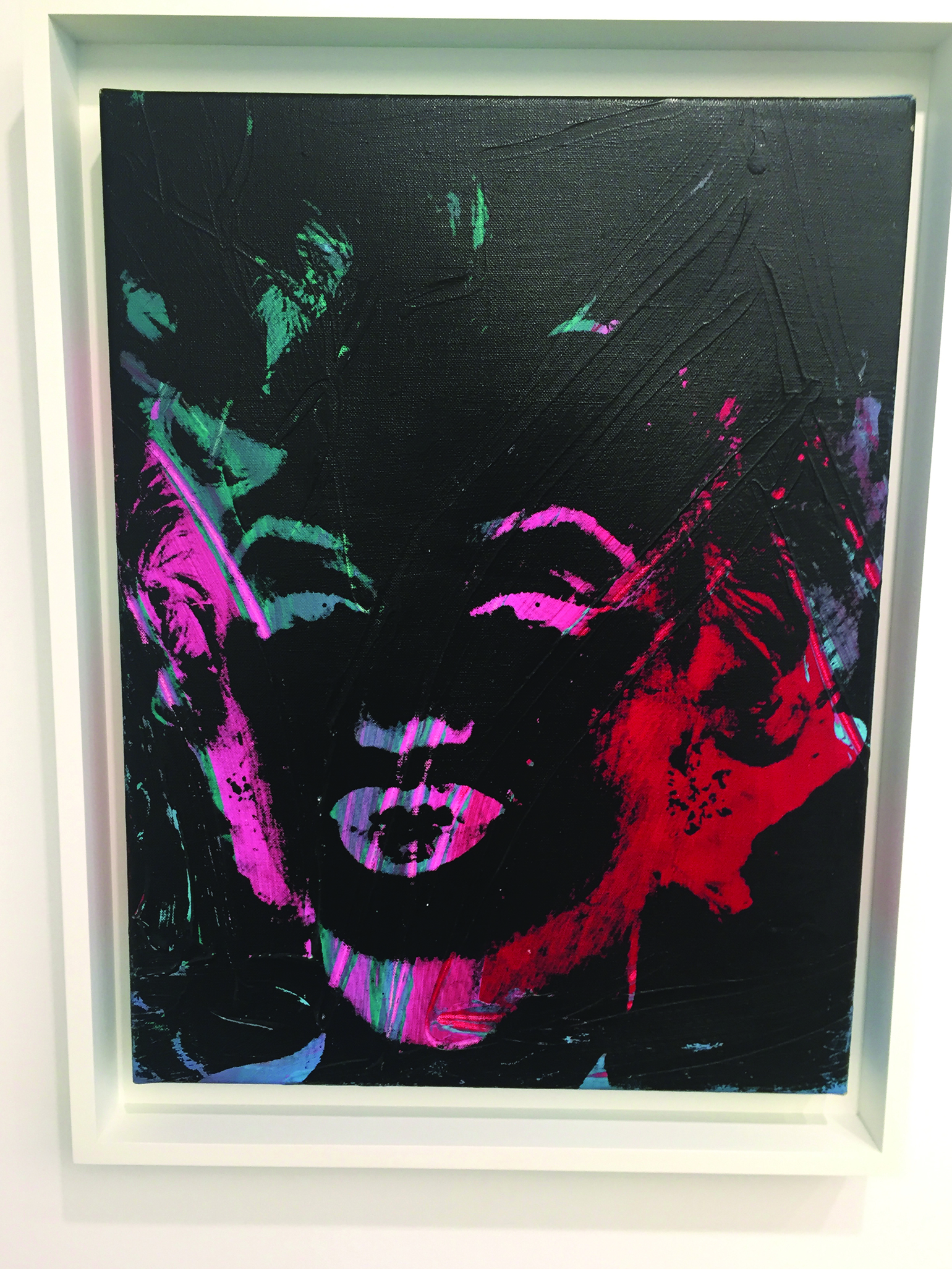

The painting—an oil and silkscreen on canvas, signed and dated in 1979 by Warhol, called 1 Colored Marilyn (Reversal Series), which sold for $1.815 million at its last auction sale in 2017—will remain displayed in a Broome Street gallery in New York City. My interest in the painting is limited to 125 shares at $20 per share. If you want to get technical about it, my $2,500 investment represents 0.125% ownership of the piece.

By making this investment, I have leapt into the future of finance, one in which investors of average means can invest in fine art, a blue-chip corner of the investing world that was previously open only to the super wealthy. With securitization, thousands of investors have an opportunity to diversify their portfolios with an asset class previously closed to them. When the asset sells, shareholders receive a portion of the appreciation.

Diversification and democratization is what this new asset class offers. The fine art market is largely isolated from the ups and downs of the S&P 500 Index and is less volatile than capital markets. In fine art, collectors recognize a tax-efficient asset with the upside of capital appreciation as part of a diversified portfolio.

Innovative fintech startups such as Masterworks, the partnership that purchased the Warhol, want a broader demographic to get a piece of the fine art action—without the risks and headaches of actually taking possession of the artwork. Owning a multimillion-dollar work of art requires insurance, alarm systems and secure storage. As a fractional art owner, I get many of the benefits—I can still visit the Warhol whenever I want—without most of the expenses.

Moneyball for the Art World

Fractional art fintechs apply big data to mine datasets of historical art sales to identify works of art that may be undervalued by the market. Then the asset is divided into securities so that average investors can (within limits) buy shares in a fund that purchases the art, safeguards it, displays it in galleries, loans it to museums and, ultimately, sells it for a profit to a collector or another investor. It’s like Moneyball for the art world, using big data and machine learning to identify artwork undervalued by the art establishment.

In operation, fintechs select an artwork its algorithms suggest is undervalued by the art world and has the best chances for appreciation. After buying the artwork, the fintech securitizes the art with the SEC’s blessing. This process falls under the new Regulation Crowdfunding rules under Section 4(a)(6) of The Securities Act.

When I indicated an interest in investing, I was asked to schedule a screening interview. Senior Vice President Michael Del Pozzo explained that while anyone, not just accredited investors, may invest in the Masterworks offering, it wants to be certain the investment is suitable. Del Pozzo made sure I understood the risks of the investment. He also explained that on occasion he’s had to decline the money of individuals he felt did not meet the company’s suitability standards.

To some people, treating art as nothing more than a commodity is off-putting. Critics say people should buy paintings if they like looking at them, but not to make money. The Village Voice disparaged this new asset class as “the best way to suck all the joy and humanity out of art.”

By this view, artworks are primarily aesthetic investments. “I feel a rather strong dislike for the narrow focus on art as an investment,” says Michael Juul Rugaard, partner with Norfico, a Copenhagen-based fintech research firm and an expert on the tokenization technology that enables investments in fractional art. “Art is about so much more than money; reducing it to a question of a good or bad investment is a bit sad.”

But that horse has abandoned the barn a long time ago. The art world has always been about more than aesthetics. The romantic aspects of collecting art have always been associated with an interest in collecting art that the market validates by assigning monetary value to objects.

Aligned Interests

Masterworks is structured to align the interests of the company with the investors. Masterworks does not realize returns until the Warhol is sold. At that point, it collects 20% from each investor’s profits. It also charges a 1.5% annual management fee to cover operating expenses, insurance, distribution costs and regulatory expenses. If Masterworks is presented with a serious offer, it’s required to poll the investors. Majority vote governs whether to sell.

To be sure, investing in art or coins or stamps is replete with risk, and Masterwork’s SEC offering circular filed in May 2019 doesn’t pull punches. Unlike investing in commodities such as gold, individual artworks are unique, and buyers cannot immediately be found. At best, investors must expect a long lock-in period. With tokenization, it may be possible that shares in these investments may eventually find a secondary market, but no such market exists today. The investment is the definition of illiquid.

That said, digital technology provides an answer to the traditional lack of liquidity. Maecenas is another fintech startup that applies blockchain technology to tokenize and digitally allocate single pieces or portfolios to several co-investors who can trade with other parties through an art exchange. While the owner retains 51% of the artwork’s value, the remaining 49% can be traded, transforming the dynamics of the market and bringing much greater granularity to art investing.

The big problem for investing in fine art, besides the large sums required to participate, is a lack of transparency on trends, values and even the provenance of artworks. Using tokenization, Maecenas is building a market-driven platform that will give investors more detailed insight into transactions and prices. The goal is a secure, open platform that serves as a distributed trust register for tracking the provenance and whereabouts of fine art.

Masterworks only generates taxable income during the tax year in which the artwork is sold and then only if the artwork is sold at a profit. Shareholders will receive a Form K-1. Masterworks issuers are limited liability corporations that elect to be taxed as a partnership. Title to the Warhol is vested in a Cayman Islands subsidiary that is taxed as a corporation. Masterworks believes this structure results in zero entity level taxation. Of course, tax consequences to investors vary with individual circumstances.

Overestimated Reward, Underestimated Risk

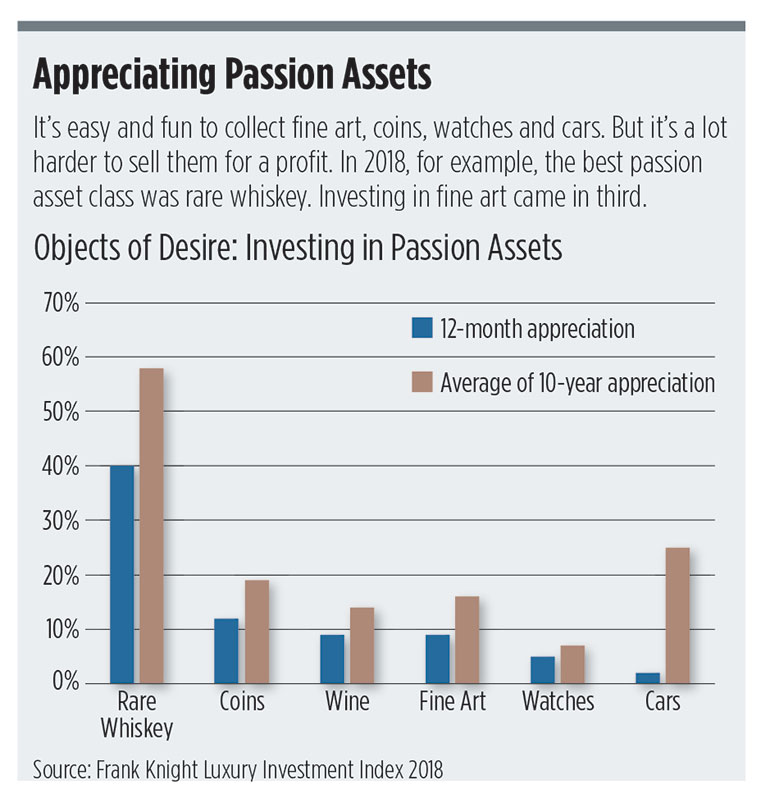

Research presented at the European Finance Association conference demonstrates two truths: Appreciation of fine art has been significantly overestimated, while the risk, underestimated. The research concludes that the true annual return of art as an asset class from 1972 to 2010 was closer to 6.5%.

The underlying cause of the overestimation is selection bias. The indexes are based on a very limited set of transactions. Returns may even be lower if survivor bias in the data is factored in. Indexes are based on sales of artworks at auction, but pieces that have fallen in value are rarely put on the block.

The analysis applies to art purchased via a fund, but there is reason to believe its lessons carry across the art world. When the study compared the investment returns and risk of all the styles of art to a portfolio of pure stocks, it concluded that art investments do not substantially improve the risk/return profile of a portfolio diversified among traditional asset classes, such as stocks and bonds.

Providers of art funds suggest that appreciation of fine art outperforms traditional assets, like stocks and bonds. A figure of 10% appreciation per year for fine art is bandied about. But there is reason for skepticism. There is nothing in the art world remotely as transparent as the S&P 500. Assuming a five-year hold, my back-of-the-envelope calculations tell me that the offering will deliver meaningful profits to investors if it beats the S&P 500 by at least a factor of two over the same period. That’s a tall order.

Is this experiment in fractional art ownership a good investment? Time will tell. As noted, the time horizon for this investment may be up to five years. When a majority of investors accept an offer and the Warhol is sold, I will report on the transaction and how my investment performed. Until then, you are welcome to view my Warhol, or at least the 0.125% of it I own, the next time you are on Broome Street in lower Manhattan. Maybe you’ll see me there.

No Comment! Be the first one.