Reviving an avant-garde in India: Reliable Copy’s (Fine) Arts Dissertations series – Features – Education

South Asia is rarely recognized as a hotbed of groundbreaking modern and contemporary art. Its nations are still on difficult paths to recovery after two centuries of British rule, Partition-related conflicts between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and the more recent civil wars in Sri Lanka and Nepal. While the region may not be perceived as a major destination in the globalized conte mporary art world, various creative endeavors—such as artist collectives, informal letter exchanges, and meetings—are prevalent and advanced. Though they flourish primarily at the grassroots level, the solidarity and alternative infrastructures that they cultivate are crucial to the region’s arts community.

I am based in Sri Lanka, which is home to only a handful of fine art schools. Students struggle due to an under-resourced education system that cannot support their pursuit of professional careers in the arts: schools don’t institute any career fairs, thesis exhibitions, or field trips, and the few opportunities for exposure remain centralized in Colombo, the country’s capital and financial center. Low budgets also prevent the cultivation of programs in the smaller cities of Jaffna, Trincomalee, and Matara, each at least a hundred kilometers apart on the country’s north, east, and south coasts, respectively. The education system also remains fraught with linguistic and cultural barriers that stem from ethnic conflicts between the Sinhalese and Tamils, which resulted in a twenty-six-year civil war that only ended in 2009.

In March of 2023, I traveled to Bangalore to meet with the founders of Reliable Copy, a publishing house and curatorial outfit based in the city. India remains the hub of artistic production within South Asia, and the differences between its arts communities and institutions and those of Sri Lanka are stark. Even so, Reliable Copy remains the only organization I’ve encountered in South Asia that is founded by members of our generation and devoted purely to books. Established in 2018 by the artists Nihaal Faizal and Sarasija Subramanian, the press defines itself as a “publishing house and curatorial practice dedicated to works, projects, and writing by artists,” and their goals remain ambitious and increasingly critical for the arts in South Asia.

In 2021, Reliable Copy commenced its (Fine) Arts Dissertations series, which republishes theses written by former fine arts students at the Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU) of Baroda. Subramanian remembers referencing these written projects while studying for her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in painting at the university. Among these texts, she encountered a wide range of unique tonalities and topics; some of the texts used conventional art-historical approaches, but many others unfolded in diaristic, semi-fictional, or stream-of-consciousness formats. At MSU, writing a dissertation is compulsory for the completion of an MFA, but the projects have minimal impact on students’ grades. Subramanian wrote her dissertation in a self-directed fashion, and was given full freedom to choose her subject, language, format, and tone. As opposed to heavily supervised processes of dissertation research and writing that are commonly practiced in arts and humanities programs, MSU students are encouraged to use the project to express themselves freely. Conventions of academic registers do not apply, and critical thinking and practical applications of theoretical and historical perspectives are encouraged.

MSU is a reputed public university in the state of Gujarat in western India, and its Faculty of Fine Arts program has always maintained this ethos of creative emancipation. Baroda College—as the school was originally named—was established in the late 1800s. In 1949, just two years after India declared independence from the British Empire, the Baroda State’s last maharaja converted the school into a university. The university’s first vice-chancellor, Hansa Mehta, was an influential activist and reformer, and one of the few women who helped draft the newly sovereign country’s constitution. Mehta shaped the Faculty of Fine Arts into a space for intellectual growth, activism, experimentation, and discourse-building. This academic culture has prevailed to the present and is easily recognized within students’ dissertations.

“Baroda has given a [sic] lie to the notion that the art school experience only stifles creativity and somehow has to be endured by a young artist, only to be forgotten gradually as a bad nightmare,” wrote Ratan Parimoo, one of the university’s first alumni to become an art historian and educator, in a 1993 essay. “But the Fine Arts Faculty premises and what I call the ‘mitti’ (the earth) within these boundary walls has worked on the psyche and the minds of the artists who throng there. To infect them and to motivate them…Baroda has had no rebels; rather, everyone is a rebel in their own way. It is in this dialectical manner that all conflicting avant-garde viewpoints function side by side.”

The school has indeed given rise to “rebels” who have achieved international recognition for their artistic talent and intellectual prowess. During the late 1950s, a group of pioneering MSU students became known as the influential “Baroda School,” which challenged India’s growing nationalistic art movements with more progressive and liberal approaches to art-making. They organized their own exhibitions and art fairs to showcase their narrative, figurative styles of painting, formulated as both a return to Indian tradition and a way out of nihilistic Western abstraction. On the same day that I met with Faizal and Subramanian, I visited the Museum of Art and Photography in Bangalore to see its retrospective of Jyoti Bhatt, who is associated with the Baroda School and currently a faculty member at MSU. Bhatt’s work as a painter and photographer engages with local cultural symbols of peacocks, lotus flowers, and deities in a cubist style, and he has documented life in rural India and at MSU for decades, always careful to consider the relation between camera and subject.

Reliable Copy emerges as part of this vanguardist legacy, and its (Fine) Arts Dissertations series resolutely upholds the school’s foundational values. The project dedicates itself to learning from previous generations of artists while also contributing new discourse to the histories of Indian art(ist)s. It is researched, developed, curated, designed, and printed in India, using readily available resources within Bangalore. The small team—which primarily consists of artists—maintains a focused vision for publishing and disseminating its titles. All dissertations reproduce their source documents with exactitude, preserving any stains, tear marks, blank pages, notations, and spelling errors that were visible in the originals. The design changes are minimal and are limited to the front and back covers, editors’ forewords, and supplemental interviews conducted by the publishers. These interviews provide the artists an opportunity to revisit their texts today, looking back on the ideas and artistic preoccupations they possessed as students and occasionally reflecting on what they might have done differently. Each dissertation’s value as a primary document is not merely preserved, as it already has been on the university cupboard or shelves; Reliable Copy’s republications enhance the originals’ meaning, turning them into a bridge between two points in time and within an artist’s life alike.

The first two publications in the (Fine) Arts Dissertations series are exemplary of the publishers’ ambitions. Sculptor’s Notebook, written in 1985 by Pushpamala N, and Urban Kitsch, written in 1996 by Praneet Soi, each bring their audience on a journey of self-discovery as their authors develop and hone their artistic interests. In Sculptor’s Notebook, Pushpamala crafts a text that is as reflexive and malleable as her multidisciplinary feminist art practice. She speaks of attempting to make sculpture within a problematic, patriarchal India, hoping to instrumentalize art to become “whole, confident, self-contained… an image of woman not as a martyr or victim (as [she] felt then), but as a strong whole human being who looked straight at the world.” At the end of her interview with Faizal and Subramanian, she invites the two publishers to “beer time,” a gesture that conveys her commitment to holding space for younger artists and professionals as both a mentor and collaborator, one method of dismantling societal barriers and building solidarity.

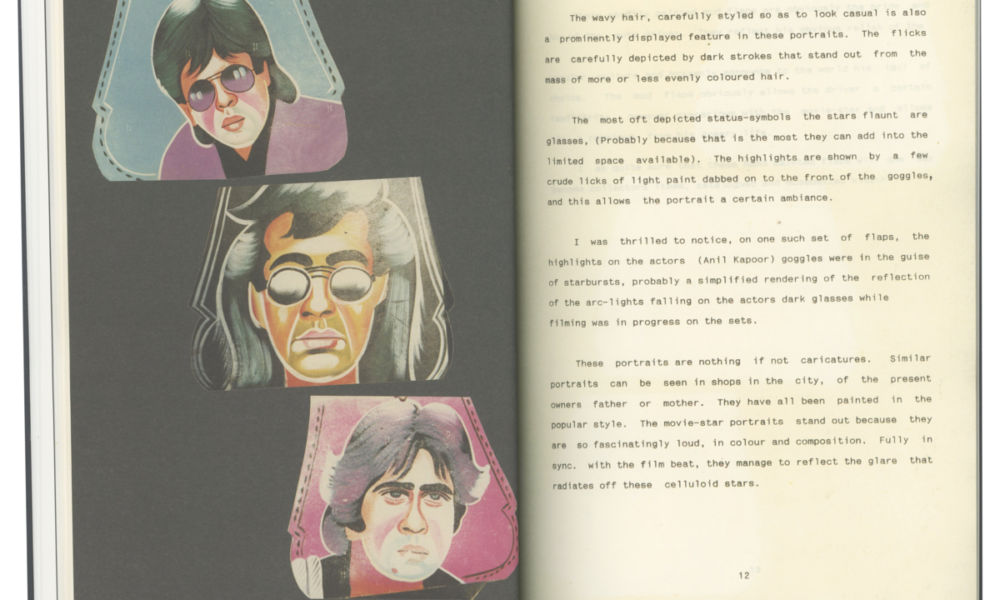

Soi’s Urban Kitsch, submitted as a requirement for his degree in painting nearly thirty years ago, details the kitsch sensibilities of local advertisements, billboards, monuments, and the architectures that he commonly encountered in Baroda. The opening line of his dissertation lays out his research objectives and thesis with lyrical, dreamy rumination. “Pondering over things in the light that illumines my minds [sic] deepest recesses,” the young painter writes, “I try and unwind the labyrinthian path that has led me to this project.” In the accompanying interview with Faizal and Subramanian, Soi speaks about his younger self being compelled to write about kitsch because of his encounters with political figures and Bollywood celebrities in branding, image building, and election campaigns full of unfulfilled promises to citizens.

While Pushpamala and Soi’s dissertations summon deeply personal observations and emotions to locate their artistic interests, the two newest additions to the (Fine) Arts Dissertation Series skew more theoretical, orienting their own thinking around broader art-historical critique. Melancholia in the Age of Mechanization, a treatise written in 1994 by the multimedia artist Kiran Subbaiah, focuses on how industrialization played a part in modernism’s “melancholia.” The text charts the artist’s intellectual and psychological struggle with pathos as he witnesses society quickly shifting from one art movement to another during the age of mechanization. Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencholia I, which depicts a woman with wings sitting in despondent contemplation, serves as a historical and affective cornerstone of Subbaiah’s project.

The Significance and Relevance of Early Modern Indian Painters to the Contemporary Indian Art, written in 1971 by the artist Nilima Sheikh, traces the British colonialist roots of modernist art in India while also scrutinizing the nationalistic, revisionist models of artmaking that many of her predecessors and contemporaries contributed to. Exemplifying the ideas she uncovers in her dissertation, Sheikh’s paintings and drawings forge a path between the modern and contemporary, invoking beauty, femininity, and traditional craft alongside more postmodern confrontations with India’s persistent woes and troubled legacies. Both dissertations are crucial testaments to how artists from India have responded to Western art movements with informed, critical insights from their own surroundings, as opposed to merely emulating them. Subbiah and Sheikh share a profound dissatisfaction with the art histories they inherited and are remarkably successful in articulating their ambitions for a different path forward.

Subramanian says that the (Fine) Arts Dissertations series will be a continuing engagement for Reliable Copy, and she hopes that it will serve as encouragement for other cultural practitioners to commence similar initiatives on local, regional, and global scales. Reliable Copy does not claim this concept as its private property; its goal is purely to develop and disseminate resources for rigorous research, critique, reflection, and awareness-building. By publishing student dissertations by influential Indian artists who are all still active today, the series forges fresh connections between India’s past and present, building a new art history from these artists’ youthful ambitions, thoughts, digressions, and vivid imaginations. Art students’ work and writing rarely reach people beyond the walls of the academy, typically languishing within library stacks. But Reliable Copy treats these texts as significant documents worthy of serious study. In addition to providing a glimpse into the artists’ early preoccupations, the texts open a window into MSU’s Faculty of Fine Arts program at various points in time. The program’s experimental principles cannot be separated from the rich history of the institution, the region, and India’s transition to independence. It pioneered a philosophy of artistic and intellectual liberty that Reliable Copy has deftly refracted.

Reliable Copy also recently received one of Printed Matter’s Volume Grants, a source of funding for publishers who are Black, indigenous, and people of color. Consequently, the publishing house made its first-ever appearance at the New York Art Book Fair this past April. Its books are now carried by Printed Matter, the French publishing house Les Presses du Réel, and the international distributor Public Knowledge Books. Having attained international circulation, Reliable Copy can share its exceedingly unique, carefully crafted scholarship with today’s generation of art practitioners, in addition to those who shall follow.

No Comment! Be the first one.