Inside Light — a Peek Into Stockhausen’s Operatic Magnum Opus

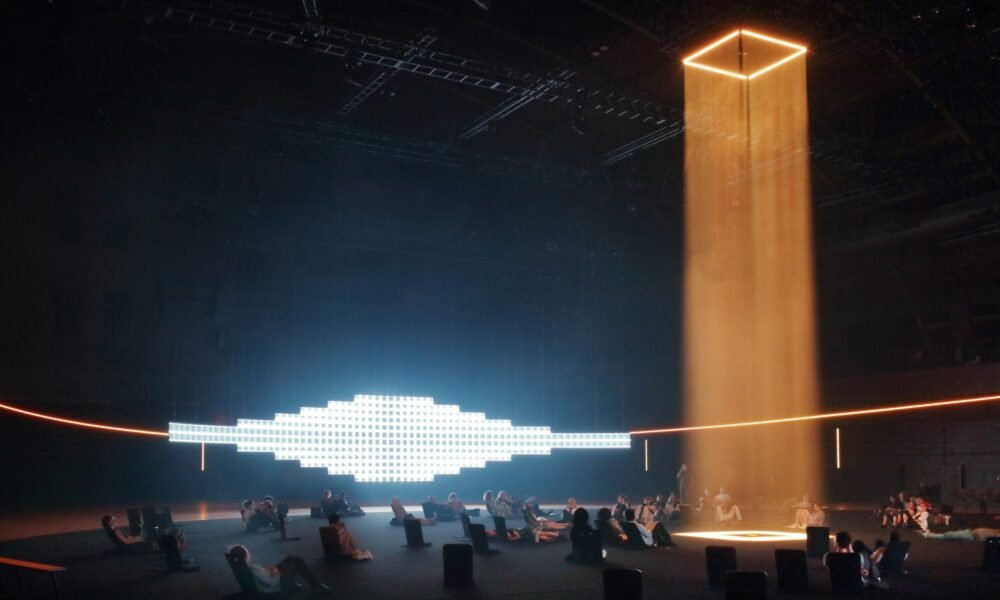

Inside Light at Park Avenue Armory, 2024. (Photo: Stephanie Berger).

Recently, Park Avenue Armory—the multidisciplinary arts space in the Upper East Side that previously housed munitions for the U.S. Army National Guard—hosted a two-part concert titled Inside Light. But this was no ordinary concert: part musical event, part immersive art installation, and part light show; it was as singular and all-embracing as the Karlheinz Stockhausen music that formed the backbone of the show. The audiences had the option of experiencing either over two nights or, as I did: a six-and-a-half-hour marathon with two intermissions and a dinner break.

The name of Karlheinz Stockhausen may be unfamiliar to fine-art mavens, but for music devotees, the late German composer remains a titan even after his death in 2007. Among his many accomplishments, he was a pioneer of electronic music, creating some of the first fully electronic compositions in the 1950s and experimenting with chance and spatial elements in breaking down all sorts of musical conventions. (In popular music, the Beatles picked up some of his innovations for more experimental cuts like “A Day in the Life” and “Revolution 9”; Pink Floyd, Kraftwerk, and Björk also count him as an influence.)

Inside Light at Park Avenue Armory, 2024. (Photo: Stephanie Berger).

Stockhausen devoted the last few decades of his life to completing Licht(“light” in English), a seven-opera cycle that, because of the variety of logistical challenges these works present, isn’t likely to receive a full staging anytime soon. One of the operas, for instance, features a scene in which all four members of a string quartet perform while taking off in actual helicopters from a field, which gives you an idea of its insane ambition. But Pierre Audi, the Armory’s artistic director and a stage director in his own right, produced a three-day festival featuring chunks of Licht—including the helicopters!—in Amsterdam back in 2019.

Inside Light, also conceived by Audi, distilled Licht even further, reducing it to a five-hour selection of mostly instrumental electronic music from the cycle. Most of the music was intended to be played in the lobbies of theaters before and after some of the operas rather than onstage as part of the action. For that reason, one didn’t need to know the plots of the operas and could simply bask in Stockhausen’s music. But for those who prefer a bit more drama in their theatrical entertainment, the prospect of basking in his slowly evolving textures for hours on end might sound like a lengthy investment of time for precious little reward.

Inside Light at Park Avenue Armory, 2024. (Photo: Marco Anelli).

Audi’s solution to that problem was to treat Inside Light as basically a visual and aural art installation. Accompanying the music—prerecorded but projected via computers by Kathinka Pasveer, Stockhausen’s widow—was an ever-shifting lighting design by Urs Schönebaum and a colorfully abstract video design by Robi Voigt. Even more installation-like was the way Audi arranged the seating in the Armory’s massive Wade Thompson Drill Hall. Around a large circle, audience members could sit in conventional chairs around the perimeter or cushions on the floor within. Furthermore, we were all given the freedom to move throughout the space, even to leave the auditorium and come back if we needed a break from Stockhausen’s brand of electronically manipulated mysticism.

Though I got up a couple of times during the second half of the marathon session I attended, for the most part, I found myself too mesmerized by the images and sounds around me to think of tearing myself away, much less leaving my floor seat. Having listened to a handful of Stockhausen pieces beforehand, I had always found his music intriguing but a bit difficult to get a grip on, his forbidding sonorities proceeding seemingly at random, leaving me somewhat lost in space. (Try his early 1955-56 work Gesang der Jünglingeif you’re looking for a taste.) However, the chunks of Licht featured in Inside Light presented fewer problems for me; at least once, I grasped that Stockhausen would take his time, drawing us in with a sustained ritualistic tone before finding variations within. It was simply up to me to find the patience in me to allow his vast electronic canvases to unfold.

Inside Light at Park Avenue Armory, 2024. (Photo: Marco Anelli).

This is where the visual elements proved to be especially useful, however. On two sets of screens on opposite sides of the performance space, Voigt used different colors and patterns in his video design to characterize each section, all corresponding to the moods Stockhausen evokes without referring to anything concrete. Even more vivid in that regard was Schönebaum’s lighting, which alternated between spotlights, crosshatched patterns, and light towers while the drill hall was shrouded in darkness, a circular light surrounding the space. Even if you found your attention to the music flagging—understandable, given the glacial tempos—there was always something stimulating to see.

None of the images, however, were enough to distract from the music, which remained the center of attention. At the very least, there were moments in these scores that represented the first time I could honestly call Stockhausen’s music “beautiful.” Here’s hoping this most recent run of Inside Light isn’t the last time these bits of Licht get a public performance, visual-art installation elements, or otherwise.

No Comment! Be the first one.